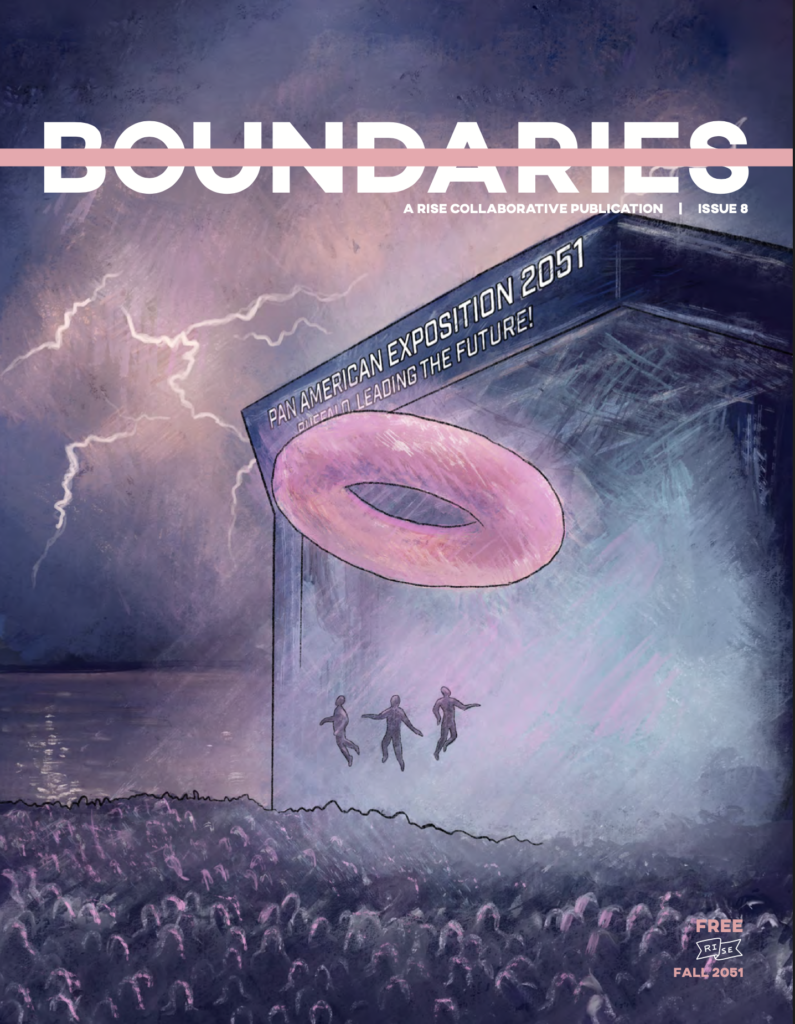

This is the digital version of Green Halogen, the futuristic article in No Boundaries magazine, released fall 2021, depicting Buffalo in 2051. Our authors were given a 12 page report compiled by area professors, researchers and non profit leaders about the city we might have by then, if we get to work now. Those authors then let their imaginations run wild.

The entire production was presented by West Side Promise Neighborhood.

This article is presented by D’Youville University and The Beer Keep.

(All references to actual persons or actual stories are purely coincidental)

Please support Rise. Order a physical copy to be delivered to you today!

Green Halogen

Written by LaGuan Rodgers

Illustrated by Renee Helda

SEPTEMBER 2051

My mother and sister-in-law have no idea what my twin brother Luther Jr. is up to. He knows I’m on the fence about the Roosevelt RX-4. It’s not to say it won’t work, but there’s some wrinkles. It’s dangerous territory, I feel, yet I said yes when he asked me to attend the press conference at the Buffalo Niagara Convention Center. Ma didn’t think it would be a good idea for me to be up on stage with him. “He’s the sharper speaker, sugar,” she said, but I knew it had everything to do with my burns.

Luther is a UB and Johns Hopkins grad, and did residencies in places like D.C. and Ann Arbor. I was almost finished at Northwestern when he met Mariah in Tanzania while both were helping out in the Peace Corps. It just so happens, she’s from Auburn, the town where President William McKinley’s assassinator got the electric chair. These days, the prisons are big on rehabilitating folks, like really sending them back out into the world with a fighting chance if there’s any fight left in them. I found a few quotes on love and put them on a crumpled piece of paper an hour before their wedding, yet I never got to speak. Our dad Big Luther, as people called him, got a hold of the mic and it turned into this long drunken prediction about the Bills going on a repeat as Super Bowl champs back in ’35. He was right on that. At age 60, Dad died from cirrhosis. Mom cared for him as best she could during the last months in the old house on Florence Avenue—maybe it was her way of forgiving him for the time he smashed the bathroom mirror with a frozen chicken, or peed on her marigolds or when those mechanic hands almost choked the life from her.

“Dr. Kaufman, do you remember?” a deep voice rings out.

At this point, I can hear the dull humming of the podium microphones. I’m scanning the wide conference room as if I can identify anything harmful and offer protection. If it’s anything like mine, Luther’s breathing is purposefully rhythmic and craving something sweet. My mother made the trip from Arizona and is sitting on my right. Since my dad passed on four years ago, she settled in Sun City. A woman who is up there has to consider her joints and spirits—her reasoning for getting a one-way plane ticket and not looking back. She said she wouldn’t have missed this for anything in the world though, except for the chance to meet the late great Alex Trebek. It was her idea for Luther and I to wear matching grey suits with knit mint green ties.

“Maybe he’s kind of tired up there, Ms. Candace?” Luther’s wife Mariah whispers to my mother.

“Or very drunk,” my fifteen year old nephew Odin chimes in, bent over, both hands rubbing his eyes, halfway off the seat.

Nothing. Just one man’s stare into a sea of suit coats and flashing lights.

“Do you remember what inspired you to dedicate your career to trauma rehabilitation,” Terry Condotta of The Buffalo News rises and sets a skinny laptop behind him. He looks around the conference hall. “Please share, Doctor.”

Luther narrows his hazel green eyes and smirks. We share our mother’s eyes, and when they meet, he blows out a gust of air that brushes his microphone, and then he begins.

“Leon Czolgosz did not kill McKinley 150 years ago, people,” Luther blurts out, shaking his fist and stiff pointer finger. Odin sighs. Mariah is just relieved he’s present. “The president died because of his doctors, specifically them poking at his wounds. They couldn’t get out of the way.”

Condotta, rather unimpressed with my brother’s social studies folklore, speaks for the crowd of attendees gathered inside. “Forgive me, but what does that have to do with your research, Dr. Kaufman? I’m struggling to find a connection.”

“In two weeks, our city will celebrate another rebirth as they did the first time when the Pan-Am Exposition put a blinding spotlight on us,” Luther says.

“Oh my God,” mumbles Odin. “Is there food here?”

“Listen to your, daddy,” my mother leans across me in Odin’s direction, waving her hand at him half serious, half playful.

“Two years ago, when I heard the fantastic announcement of another expo, I knew it would be the perfect arena to reveal something to the world on such a grand stage and I wouldn’t have it come to light at any other place than our hometown—a place I consider to be the greatest town in the entire country. I mean, I would know, I’ve been to quite a few.” Luther says the last part with a wink. Mariah looks at me. Just let him go, I think to myself.

“Mr. Kaufman,” a new voice finds its way over the wave of bodies and sleek electronics. A female reporter, slight in frame with a climbing tone, stands up. “Alicia Karlson of Buffalo Spree Magazine, here. Are we at liberty to get some sort of inkling?”

“I’m no showman but . . .” Luther says, his smile curling at both ends of his mouth. “All that I will say is our minds can be gardens.”

“At what is shaping up to be a carnival-like atmosphere, the world could use some clinical magic,” Karlson says, waving her pen around in tight circles like a makeshift wand.

“No magic involved here, ma’am,” Luther shifts his weight to the other side, he’s in his comfort zone now. “I can say this without fear or doubt: for the past five years, I’ve tested people of all backgrounds and stories—you name it.I believe this with every atom: it begins with our memories! Oh, and by the way, thank you Mom for some great ones.” He blows a kiss towards Mom. She plucks it out of the air and brings it to her chest as if she’s gathering blackberries from a leaning bush.

Mariah has let one foot come out of the blue sandal tucked under her seat. She leans in and whispers to me, “He sounds like a ringmaster with a microscope.”

Mayor Helen Maung, who hasn’t uttered a word since the introduction, looks at some other local officials and correspondents, then nods pleasantly at Luther. “If we can take anything from this time together, it’s that you sure know how to drum up curiosity. We hope your diligence and efforts advance society in some way, exemplifying Buffalo’s gritty spirit.”

“Mayor Maung if I may?” my brother asks as diplomatically as he can. The Mayor nods. “Years ago I couldn’t have imagined the city’s poverty levels are what they are currently: wealth is more evenly distributed, crime much lower than days past. Our neighborhoods are breathing rainbows, dare I say safe, healthy and harmonious. Heck, some nights we forget to lock all our doors while we snooze! The drugs my brother Donovan and I could’ve found readily available on choice corners and at trap houses as kids are virtually gone now. My father Luther Bryce Kaufman Sr. used to recall days when Buffalo, New York was an afterthought to the rest of the country, a collection of underdog rants seemingly trapped under the confines of a thick snow globe. Yet look at us now. No longer laughing stocks, our teams are multi-year champions. In 1901, people traveled here to see the biggest concentration of electricity at one time. When I present my Roosevelt-RX4 machine, its beam will illuminate science!” Without the slightest salutation, Luther makes his way towards the exit, and we follow.

Early the next morning, we’re sitting in a booth eating donuts at Paula’s. It’s our Saturday thing—he, Odin and I. I rode my refurbished ten-speed over to their larger than necessary house and we caught the bustling Rapid Transit to the location inside Buffalo Central Terminal. These Kaufman Commissions, as they’ve been dubbed, are seemingly 5 percent bonding, 92 percent research, and what’s leftover is seldom quantified.

“Do you remember when there were only two locations to get these sons of bitches?” Luther asks me.

“Yeah, one on Sheridan, the other in West Seneca,” I say, breaking my red velvet ring and plopping a chunk into milk.

“There was one on Main way out.” The doctor peeks into the half-open box, and pulls out a cheesecake cruller. “But Dad never took us there.”

The left side of my face and neck have feeling this morning, so I scratch just for the sake of sensation. Odin doesn’t even stare at me like he used to when he was younger.

Luther and I were 12 on that spring Saturday when it happened. Soon as the weather broke, we hit the driveway to test out these skateboards we’d jotted atop our previous Christmas lists. Neither one of us could hold up any length of time without kissing the asphalt, but it gave us something to do. Dad had come home early from the car shop for what he called quality family time, and he was supposed to take us somewhere that was a surprise: mom wouldn’t tell us where. “You fools better eat before we go anywhere,” he said earlier, with that gruff in his throat we’d heard before. The whiskey bottle hit the linoleum and shattered, then I ran inside. There he was with a steak knife pointed at Mom’s stomach, right at the belt line, his other hand pinned her up against the wall across from the stove. I knocked the knife to the floor, and more surprised than anything, my father went for me. He pushed me and I slipped over the broken shards, headed for the stovetop and its frying pan of hot grease. I just remember how my hand hit the thick black handle before the liquid splashed on to me. Luther offered no help in the tussle and only came out of our bedroom once he heard my screams. My mother didn’t want to raise us alone, so everyone stuck to the same story when protective services showed up on the scene days later, which was me riding a skateboard through the kitchen during a dinner prep gone wrong. A few grafts and visits to plastic surgeons and it never was brought up much after. I remember that doctor’s look when he saw my burns—that look someone gives when they know a thing won’t ever be the same, and all they can do is talk calmly.

When our father’s lips weren’t wrapped around a liquor bottle and his fists were quiet, he was frosting on the tallest cake. There were some good times like the family board game nights on Fridays, The Festival of Lights treks to the falls during winter breaks. When we wanted to hate him, we’d come back to those late afternoons when he’d pull into our crumbling driveway just to take us for a ride with no real destination other than to feel the wind at our foreheads.

“How’s the powdered loganberry one, son?” Luther wants to know.

“It’s alright,” Odin shrugs, exaggerating the chewing motion. I stop dunking and pick up my milk to chug some.

“What happens when a cow drinks her own milk?” Luther asks us. His eyes are big as plums with anticipation.

“Wait . . . what?” Odin responds, lost in powder.

“It goes in one end and out the udder!”

The boy finds no joy in Luther making a milking motion. He grimaces in disgust and leaves for the restroom. I wait until the coast is clear.

“Are you really going to go through with this at the expo?” I raise a brow, and he knows where I’m going.

“Umm, yeah . . . my machine…I mean, our machine will erase people’s bad memories, like all the bad shit that ever happened in someone’s life is all gone, wiped out, completely.”

“Besides Baw, who has even used the thing?” I say, pissed off, trying to lower my voice. “It’s a lot to risk.”

Mom told us some toy called a View Master was a wave back in the 80’s, and she’d given me the one she’d kept in the attic from her childhood. “You’ll find some use for it,” she said, pulling it from her bag the day I drove her to the airport. When Luther began tinkering inside people’s heads, he requested we work together and we patterned the invention to resemble it. I provided spare metal pieces, small motors and wire controls for his RX-4, nothing more. “Are these to scale?” was his usual question. “In the name of Allentown, tell me why you gave up mechanical engineering?” he’d say.

“You’re attempting to take people’s stories from them, strip them of what’s whole,” I say. “Is that what you want?”

“No, I’m attempting to make people feel whole again.”

I shake my head. “Will you please─” Luther begins, yet stops. Odin is coming back to the table.

Before we leave, I take an assorted baker’s dozen to go so I can put them on the front counter at the bike shop for afternoon pick-ups. Po Baw, this Burmese guy, who stabbed his father and did ten years, facilitates the refugee community garden next to me. He makes it a point to come inside at closing time every Saturday to take a donut and reminds me the shop was once my father’s mechanic garage. Luther’s intense testing began with him shortly after I quit my engineering gig.

On the way back, Luther and I split a glazed twist. Odin laughed the day we told him that when we were his age, the train used to only travel down Main Street, and not the length of the whole street at that. Nowadays, the people have got on board against emissions, so folks who ride bikes like me, or walk, don’t stick out.

“Tell me what memories come to you, bro,” Luther says, pointing to my half.

“It’s a damn donut,” I say. “Sugar, cholesterol, a couple less years. I don’t know.”

He offers nothing, just another blank stare into the blurred sheets of colored walls whizzing by in frames within the train’s smooth motion.

We got back to his house. Mom is on the porch swing, an iced tea can and bottle of turmeric capsules next to her on the short end table. She wants us to sit and swallow up the early September sun with her. Luther puts his arm over her shoulder and hands her a plain ring donut. No one gives me a major stink about grabbing my ten-speed and getting to work. “Later, right?” the doctor asks me. “I’ll be there,” is all I say.

A brake cable set replacement and crank arm adjustment were the last bike jobs before closing. It’s been a whole afternoon, yet no sign of Baw, and I’m close to throwing out the last donut. Then Luther walks in, carrying a white velour pouch. I turn my back to him and face the side window. Outside, I can see the metal posts the refugees and college volunteers used to keep their tomatoes and bell peppers upright—the sun’s diamonds hitting each piece on their colorful surfaces. My eyes close to the sound of kids playing a game that I can’t figure out on the other side of the street. The games are usually noise to me, but today it sounds like music.

“I need you up there with me,” he begins.

“You can’t alter what happens in this world,” I say. “You have a case study, sure. What gives you certainty?”

“Baw’s readings and own account show no recollections of childhood pain or when he─”

“That scene is all yours in a few weeks.”

“Come on, man,” he pleads.

“It’s not my scene,” I yell.

“Ok then, what is your scene?” He’s right up into my chest now. “This? This shithole of metal, gears and how come’s? You gave up a blossoming career to retreat here to fix fucking bikes in a place where God only knows why.”

“A goddamn coward, why didn’t you help me?” I explode grabbing a fistful of his shirt. His breath still carries the crusted sugar from this morning.

“What do you mean? We’re a team.”

“I tried to hold him off, and you went into a room and hid like some fox.” He knows where I’m taking it.

“It was so long ago,” Luther says. He isn’t trying to undo my grip.

“It’s today. Even when it feels like yesterday, it’s today.”

“I block it out, or I try to,” he says. I still haven’t let go of him, yet. For the first time that I can remember, there are tears crowding his eyes and coming down. “If you want me to say fear took over, I’m guessing that’s right. I know I’m on to something. Let me help now. It’s not too late.”

Finally, I let him go.

Again, he tells me how he wants us both on the stage to reveal the magic—the back stories, charts and detectors that will authenticate the mission. Like some keeper letting a snake from its sack, the doctor loosens the drawstring of the pouch and handles the metal. He flips on the side power button, and almost immediately this green light floods the floor, darkening our sneakers. For whatever reason, I can’t help but stare at the halogen beam. It’s green like rolling hills of undisturbed grass, greener than emeralds hardening in Alaskan snow. I’m trying not to blink. I inch up even closer. It’s as green as fresh mint with an aroma that tumbles around the nostrils and signals an endless summer. Green like my eyes, Luther’s and Ma’s. At last, I’m made to blink before I extend my hand to touch it.

I put the machine up to my eyes. “Take a deep breath,” my twin says. Then everything becomes a cool black.