Examining Buffalo’s failure to contain its sprawl, its negative effects, and the successful plan Portland, Oregon implemented decades ago.

By Chuck Banas

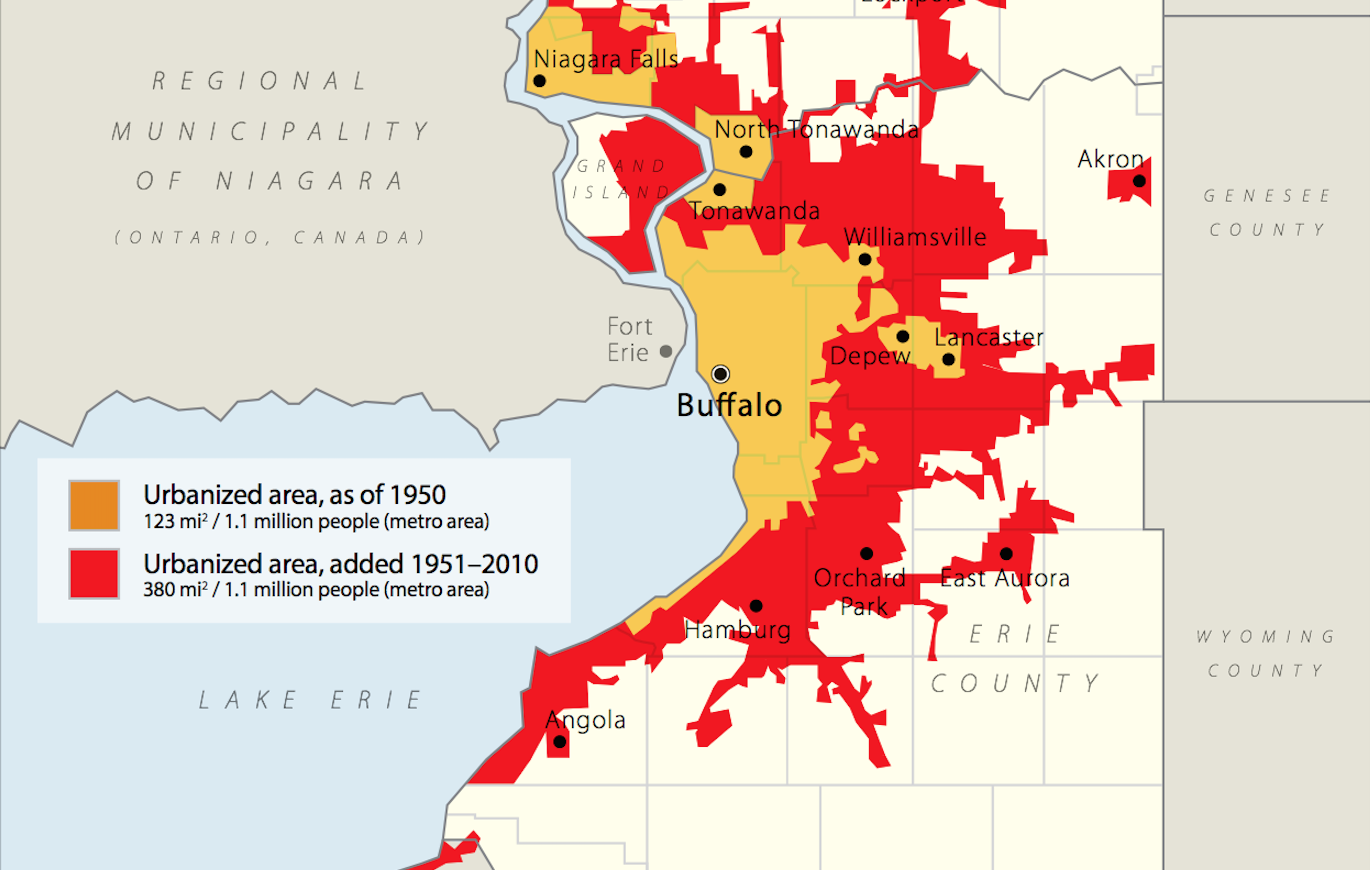

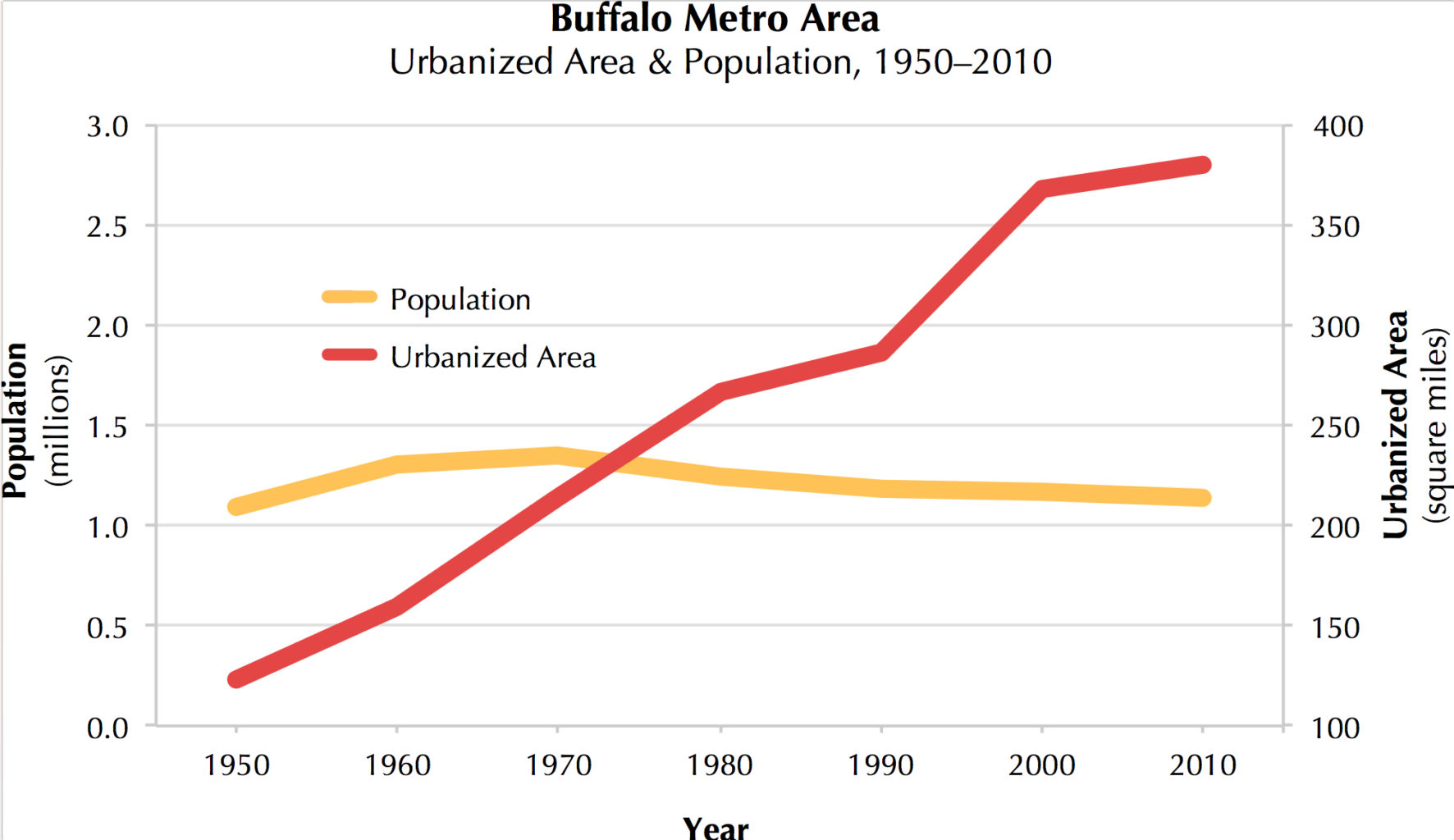

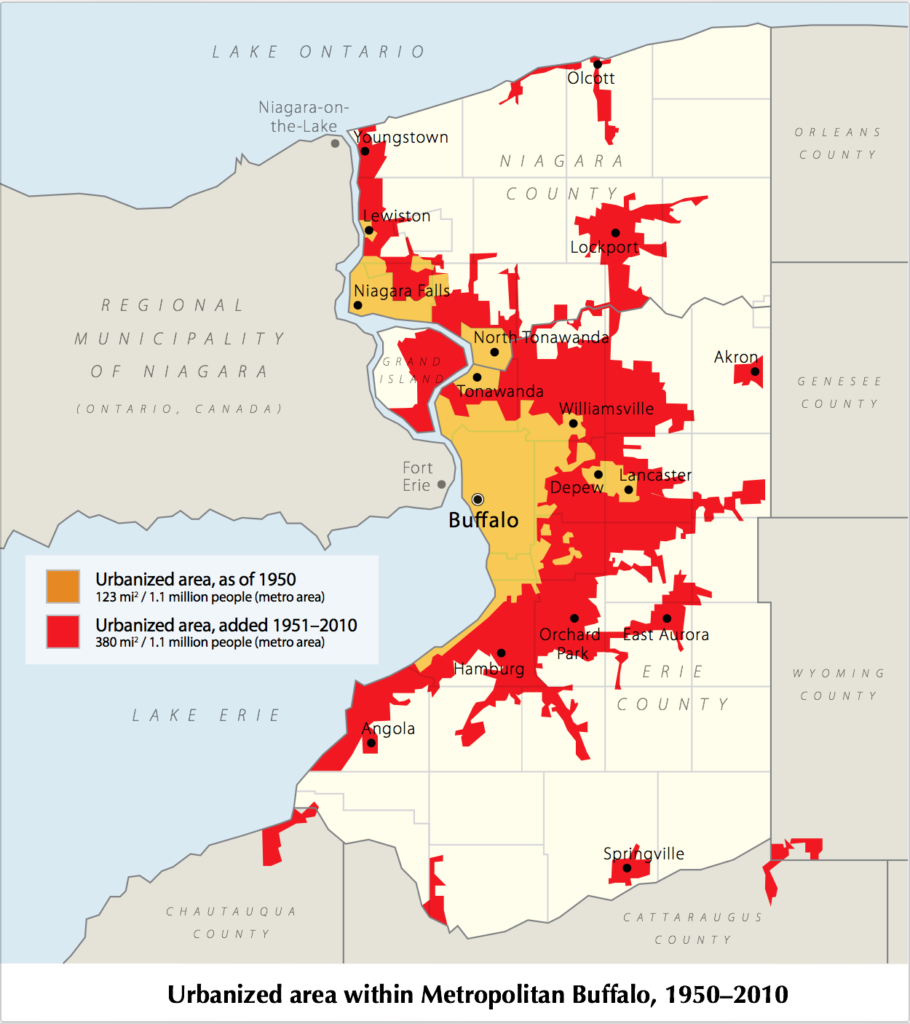

Buffalo is experiencing a rejuvenation of sorts, and there is reason to think the region’s long decline is ending. New demographic trends belie the trope that the region is getting older and poorer. For the last decade, the Buffalo area saw one of the highest increases in college-educated Millennials in the nation, and for the first time in decades, the region’s population is younger than the national average. This has been accompanied by nationally significant gains in income and productivity.But not all the news is good. While there is a renewed sense of civic confidence, the regional recovery is distributed unevenly and still appears fragile. Another old trope common to Buffalo and the rest of the Rust Belt is that of population loss. But this has actually never been quite true. The Buffalo region has maintained roughly the same population since the 1950s. Yet during this period, the area developed over three times the amount of land for the same number of people. This created a series of complex problems, including a larger tax burden; neighboring cities and towns competing with each other for smaller slices of the same pie; a massive racial and economic divide; and urban decay not just in the central city, but creeping into Amherst, Lackawanna, Cheektowaga, and West Seneca. Other cities, like Portland, OR, share similar foundations to Buffalo, but have made better choices regarding regional planning after deindustrialization. By looking at Portland from the 1970s until today, we in Metro Buffalo can start to tackle the similar challenges of city-building and sprawl with comparable success.

A mercifully brief explanation of sprawl

Urban sprawl, often called suburban sprawl, suburbanization, or simply sprawl, refers to the uncoordinated expansion of population from a central city into low-density, single-use, and typically car-dependent pattern of development.Since 1950, Buffalo didn’t shrink, it spread-out. Every new development on the urban fringe means disinvestment somewhere else—usually in an older, more centrally located neighborhood. Thus, much of our regional economy is at best a zero-sum game. This is actually worse than zero-sum— it’s a negative sum game. As development sprawls, the same number of people have to pay to build and maintain ever more stuff. Roads, sewers, bridges, electric lines, schools, police, and all of the other necessary infrastructure doesn’t pay for itself. While each municipality naturally behaves in its own self-interest, no definitive entity with appropriate power considers the bigger picture. What’s good for one community can be bad for all of us in the long run. In a region of multiple independent, overlapping municipal actors, local economic development is cutthroat and cannibalistic, with towns and cities poaching development from one another. Real estate developers play one municipality against another to get the best public subsidy, eventually costing taxpayers even more.

How did this happen?

Suburban sprawl here and across the nation was not a product of choice and neither was it a coincidence. It wasn’t simply suburban sprawl, or the invention of the automobile, or pent-up post World War II housing demand, but an intersecting set of public policies and other large government interventions.The period following WWI was an era of large state and federal government interventions. Public projects and policy reforms were enacted, often based on the fear that the nation could relapse into another depression. Combined with the experience gained in large-scale public/private collaboration during the war, this created a series of new regulations and national infrastructure programs to try to manage the economy and ease the transition to peacetime. Indeed, these policies helped facilitate the nation’s postwar boom, putting millions of people to work building the new suburbs: highways, roads, utilities, civic buildings, shopping centers, and suburban housing itself. These enablers included the national highway system, subsidized government loans for new suburban homes and businesses (while denying the same financing to older neighborhoods), and notoriously destructive projects of the “urban renewal” era. These irreparably damaged, and in many cases destroyed, older neighborhoods and downtowns.This new development was almost universally built on the standard suburban template: low-density, monofunctional, and car-dependent. The auto industry and the national economy certainly benefitted further, as every family was required to buy and maintain at least one car to be able to live in these places. But when compared to older, traditional American neighborhoods, suburban sprawl has intrinsic costs: typically consuming more land, requiring more public infrastructure, costing more to maintain publicly and individually, and returning fewer taxes per capita.

Sprawl also represents an environmental challenge, causing more pollution and requiring far more energy and other resources to maintain it.Suburban sprawl in the United States is also overwhelmingly populated by the white middle-class. This racial and economic segregation was essentially baked into formative public policy. Legal (and sometimes illegal) racial requirement stipulated that African Americans and other minorities were categorically refused access to suburban mortgages, just as their older urban neighborhoods were denied the same federally subsidized financing so freely available to suburban whites. This left most minorities trapped in older neighborhoods that soon became blighted, in large part, because the government decided they were not worth the investment.This tended to deepen the nation’s economic and racial divides, if only for one reason: the primary mechanism by which the aspiring American middle-class is able to build wealth and keep itself out of poverty—the equity embodied in the family home—was denied to several generations of postwar minorities. By the time lawmakers removed discriminatory lending from law, policy, and mostly from practice in the 1970s, the problems of racial and economic segregation that it caused for the inner-city were too embedded to be easily reversed, and many urban neighborhoods slid irretrievably far down the slippery slope of poverty.Th is sprawl cycle has continued since World War II, as most cities accumulated several rings of suburbs extending many miles into former countryside. Nowhere is this vicious cycle more apparent than in many older, inner-ring suburbs. These places are now experiencing the same problems of disinvestment and blight that cities experienced decades before. Sprawl has become the common enemy of both cities and suburbs.

The “Real City” of Buffalo

As residents of Greater Buffalo, we share a common regional identity. We participate in the same regional economy. We attend the same cultural events and use the same set of public institutions and amenities. Practically, the only relevant social and economic unit is the region, or more specifically, the metropolitan (or “metro”) area. The municipal entities within the metro area are effectively districts or neighborhoods within the “Real City” of Buffalo.While regions are integrated socioeconomically, most are fragmented politically. Only a handful of U.S. metro areas have some sort of metro government, such as Portland, Indianapolis, Denver, Louisville and Miami. While these entities’ legal structures vary considerably, such regions are generally more economically successful than those without regional governance.

In the Buffalo area, talk of a regional approach has centered mainly around the benefits that sharing or consolidating services would bring. Certainly, tax dollars would be saved by reducing needless duplication and increasing the economies of scale. But David Rusk, a former Albuquerque mayor who has become an expert on urban-suburban sprawl, further asserts:“It is not service inefficiency, but regional ineffectiveness that is the ‘real city’ of Buffalo’s great challenge. For example, having several municipalities share road maintenance equipment promotes greater service efficiency, but implementing an anti-sprawl, regional land use and transportation plan so that fewer miles of new roads are built that must be forever maintained leads to greater regional effectiveness. Centralizing criminal investigation resources among police departments increases service efficiency, but instituting a regional, ‘fair share’ housing policy that steadily eliminates high-poverty conditions that generate much criminality creates greater regional effectiveness.”Yet in the Buffalo region, there is almost no regional coordination between these “small box” entities of municipal government. Each of the 64 individual municipalities in Metro Buffalo plans and develops independently, largely without regard to its neighbors. Th is is unlikely to change anytime soon. As a “home rule” state, the New York State constitution prohibits regional government, and there is virtually no mechanism at the state level allowing municipalities to effectively manage sprawl. But state law does allow inter-municipal cooperation, which, if implemented locally, would be a significant step in the right direction.

Portland’s Urban Growth Boundary

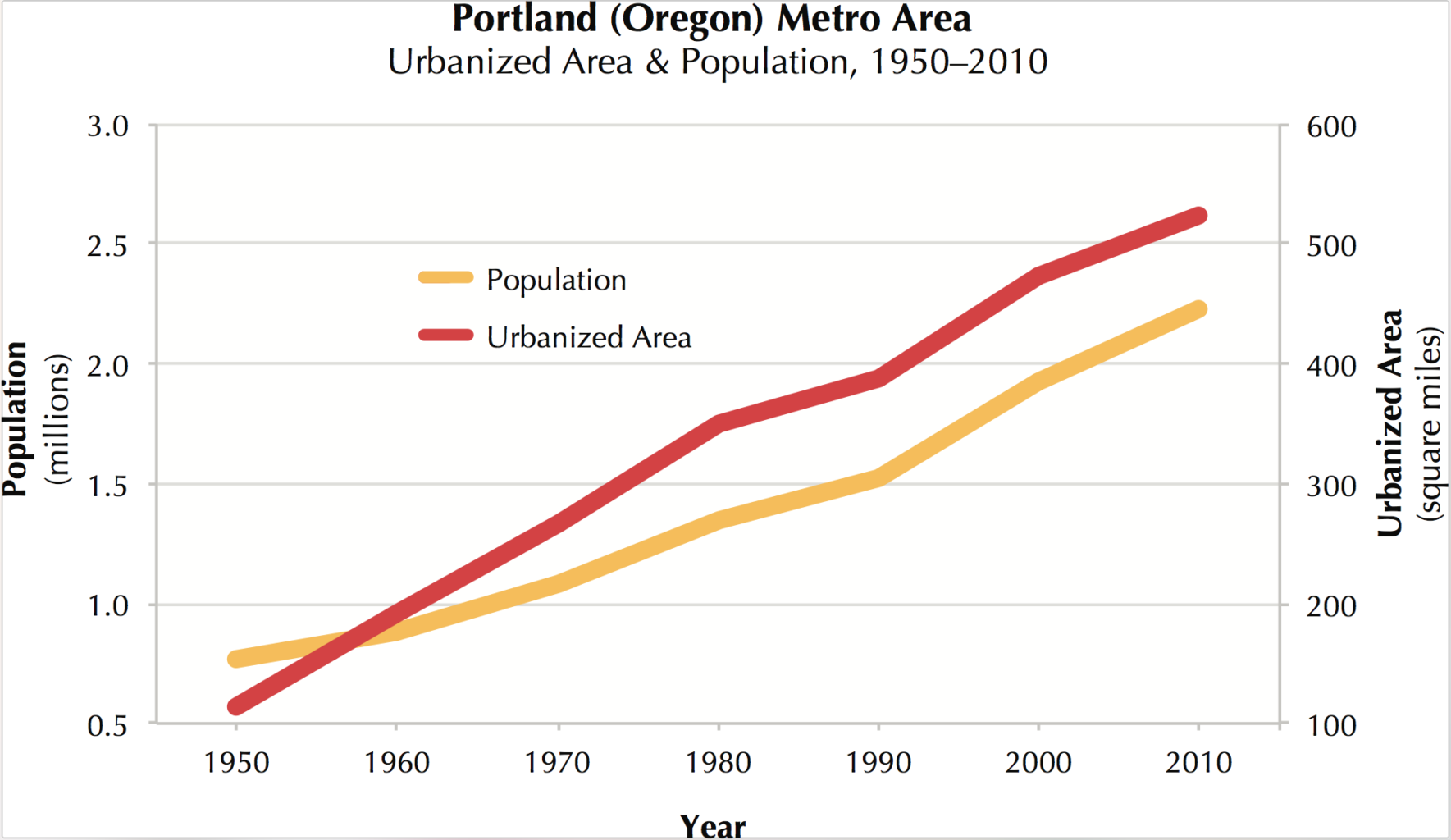

As we seek to create a robust and sustainable economy in Western New York, lessons learned from Portland are as relevant as ever. Portland is a good comparison to Buffalo, as it is our peer in many ways. They are waterfront cities that grew on a base of industry and trade, and aft er World War II, suffered similar declines from deindustrialization and suburbanization. Yet starting in the 1970s, both regions made very different choices, and have been on starkly divergent paths ever since.Among urban planners, the concept of an “urban growth boundary,” or UGB, is considered one of the most effective ways to curb sprawl. Essentially, the growth boundary is a line drawn around a metro area; outside of the line development is discouraged or prohibited, and development inside is allowed.In 1973, Oregon became the first state to adopt growth boundaries, requiring every city in the state to draw one. Oregon Governor Tom McCall, a Republican, led the effort to reform the state’s planning efforts in what has been called a “rare moment of bipartisanship.” The goal was to limit—but not ban outright—uncontrolled development that threatened Oregon’s farmland, forest, and natural scenery. Suburbanization siphoned population and investment from Portland and other older cities. McCall worked with legislators, environmental groups, and farmers to win a new and innovative institutional structure for statewide urban planning.The legislation created 19 statewide planning goals. Simply: cities must have room for 20 years of growth inside their UGB. Portland’s boundary is managed by Metro, the regional government, and adjusted every six years, if necessary. Portland created Metro, along with its UGB, in 1979. Since then, the boundary expanded about three dozen times, with most increases less than 20 acres. Today, it covers about 1.5 million people, or about 68%, of the 2.2 million people in Portland’s fast growing metropolitan area.

The difference between Buffalo and Portland is that the 700,000 people living outside of Portland’s UGB have built their homes and communities without subsidies.

In Metro Buffalo, the water, sewers, roads and services of our ever-expanding sprawl have been subsidized by the tax dollars of everyone in the region.According to Tom Reid, a planner in Portland, the idea was to steer development away from the urban edge and toward existing urban centers within the boundary, “Where growth is supposed to happen.” For the most part, it worked. “Ninety-four percent of growth has occurred in the original 1979-established zone.” Relations with developers can be occasionally temperamental, but this hasn’t slowed Portland’s housing market, one of the hottest in the nation.Metro limited the tax base-depleting factors of sprawl and blight, and allowed Portland to make significant, longterm, strategic investments. Perhaps the most important investment is regional transit and bicycle infrastructure, making the area one of the best connected, most livable areas in the country.

This helped build a valuable, dynamic, and sustainable economy. Portland became one of the most desirable and attractive cities for young entrepreneurs and other business.Strong regional governance has not only helped Portland recover from decline, but so far it has kept it from becoming a victim of its own success. The Portland economy has been booming for several decades, but only recently has housing affordability become a problem. For now, this has only affected the urban core. As Portland proper has become increasingly popular, homes there sell for a average $27,000 premium over homes in the suburbs. Today, unlike most U.S. cities, the central city of Portland has virtually no blighted, impoverished neighborhoods. And there is still ample room to develop within the growth boundary on the periphery—enough that, for now, Portland has decided not to expand its UGB.

What Can We Do in Buffalo?

The idea first floated in the late 1990s was to utilize Erie County as an entity of regional government, functionally mimicking some of the best practices of regional planning in cities like Minneapolis or Portland. By granting the county authority to do effective regional planning, the county would enter into an agreement with most or all of the county’s municipalities, granting certain specific powers, particularly the authority to curb sprawl and direct transportation and other infrastructure investments. Under the compact, affected cities, towns, and villages would be required to revise their local plans and zoning to conform to the county’s land-use and transportation plan.To ensure that benefits are shared equitably, a property tax base sharing program has also been discussed, similar to the arrangement that has been so successful between Minneapolis–St. Paul and their surrounding suburbs. Combined with a “fair share” mixed-income housing policy, this approach could begin to lessen economic segregation and reduce concentrations of poverty.In the Buffalo area, a changing demographic brings with it a new spirit of optimism, common sense and open-mindedness. Th ere may be a good opportunity to try again soon.

Want more from Rise Collaborative? Check out our podcast!

#LIFTED podcast lives on iTunes and Stitcher and EVERYWHERE else. Please listen, subscribe, review, and enjoy.