This article is a continuation of author Caitlin Hartney’s printed piece, “Site of Reckoning: The Enduring Legacies of Fillmore and Roosevelt.”

Author: Caitlin Hartney

Photography Courtesy Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center

Twenty-some miles north of Buffalo, a museum complicates preconceived notions of the Underground Railroad.

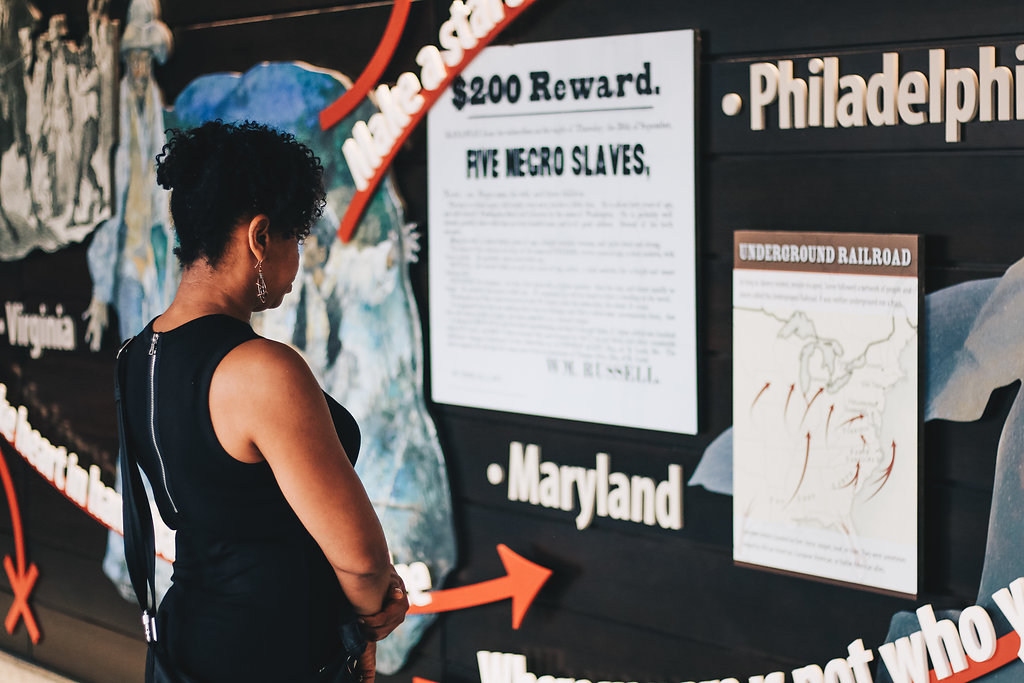

In the lieu of romanticized, text-book accounts of white abolitionists liberating despondent slaves, the recently opened Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center showcases the bravery and heroism of freedom-seeking enslaved people and the free black Niagara Falls residents who helped them abscond to Canada.

“The Underground Railroad has a very cookie-cutter narrative, which is, generally speaking, white saviors from the north rescuing African Americans through tunnels and attic spaces,” said Ally Spongr, the Heritage Center’s director and curator. “There is truth in some of that, but it’s certainly not the full story, and it’s definitely not our story.”

Instead, the story at the Heritage Center focuses on the well-organized network of black waiters who served as primary agents of the Niagara Falls leg of the Underground Railroad in the decades preceding the Civil War. During that time, the Cataract City served as one of the country’s most important gateways to freedom in Canada, where law prohibited slavery and the extradition of freedom seekers back to the United States.

Niagara Falls’ significance to the Underground Railroad can be attributed to its siting at a convergence of integrated roadways and, after 1855, rail lines that made it highly accessible from points across the east coast. Furthermore, its natural geography offered a narrow crossing point to Ontario by ferry or train, adding to its appeal. As an international tourist destination with a sizable free black population, it was also far easier for freedom seekers to blend in with the crowd and move about the city without incurring great suspicion. But it was the organized efforts of the black waitstaff at the Cataract House, a world-renowned, destination-worthy Niagara Falls hotel, that perhaps most prominently set it apart from contemporary border communities.

These waiters formed a skilled brigade that operated with military precision to daily serve elegant, highly orchestrated meals to elite guests. Their rigorous training and discipline may have also been instrumental to their concerted efforts to help emancipate an untold number of freedom seekers.

“The waiters were unique in that their work in the service industry allowed them the opportunity to interact with travelers from all over the world,” said Spongr. “They had access to southern enslavers who brought their enslaved servants with them, and they were also able to reach a large abolitionist communication network because of travelers coming to Niagara Falls. They navigated between the oppressors and the oppressed.”

At the Heritage Center, tales of their heroic deeds, including instances of organized physical resistance to slavecatchers, are brought to light by way of visual, auditory, and textual mediums designed to engage visitors with a reconstructed Underground Railroad narrative—one that highlights the feats and points of view of marginalized historical actors, who, for too long, have been relegated to passive and auxiliary roles.

The museum’s exhibits challenge visitors to cast aside what they may have learned in grade school to think about the Underground Railroad from a new perspective. It’s a disruption of the historical status quo that required purposeful design and presentation that considers how people connect with history.

“We were very attentive to our language choices, ensuring that African Americans had agency in the way the text was written,” Spongr explained.

Instead of saying “slaves were brought to the Cataract House by their owners,” for example, a panel at the Heritage Center reads “Freedom Seekers often arrived in Niagara Falls as the captive servants of southern enslavers who stayed at this world-class hotel.”

“Although subtle, the agency or power is shifted away from the oppressors,” said Spongr. “We felt that this slight shift makes a difference in how the history of oppressed groups and individuals is told.”

Aware that visitors would want to see the faces of the people whose stories are being told, Spongr’s team also made careful design decisions regarding images. Because only a single sketch of one actor, long-standing head waiter John Morrison, is known to exist, the Heritage Center installed slow-animated watercolor murals to depict its black protagonists. The effect feels timeless and authentic, despite being modern interpretations of historical events.

“At a lot of Underground Railroad exhibits, you’ll see a picture of a safehouse and white abolitionists because curators are using the images available to them.” Spongr explained. “That stuff matters. If you’re going to tell history by showing the image of a white abolitionist, then that’s the focus, regardless of what your actual intent is.”

In her statement, Spongr speaks to the reality that museums are not neutral, even—perhaps especially—those museums that seem to present a traditional, straightforward narrative. That’s because our present institutions are largely “straightforward” from a position of power and privilege. They classify, display, and present from a white, male, cis perspective that, at best, tells only part of the story. The bias is ingrained, and it serves to perpetuate longstanding power disparities, even if unintentionally.

The Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center and its focus on previously untold stories is a counterforce to that imbalance—one that Spongr hopes will leave a strong impression on visitors.

“I’d like visitors to consider a new perspective,” she said. “It would be great if every person learns how history connects to the present day, walked out, and went and changed the world. But even thinking differently makes a difference.”

Learn more about the UGGR Heritage Center here.