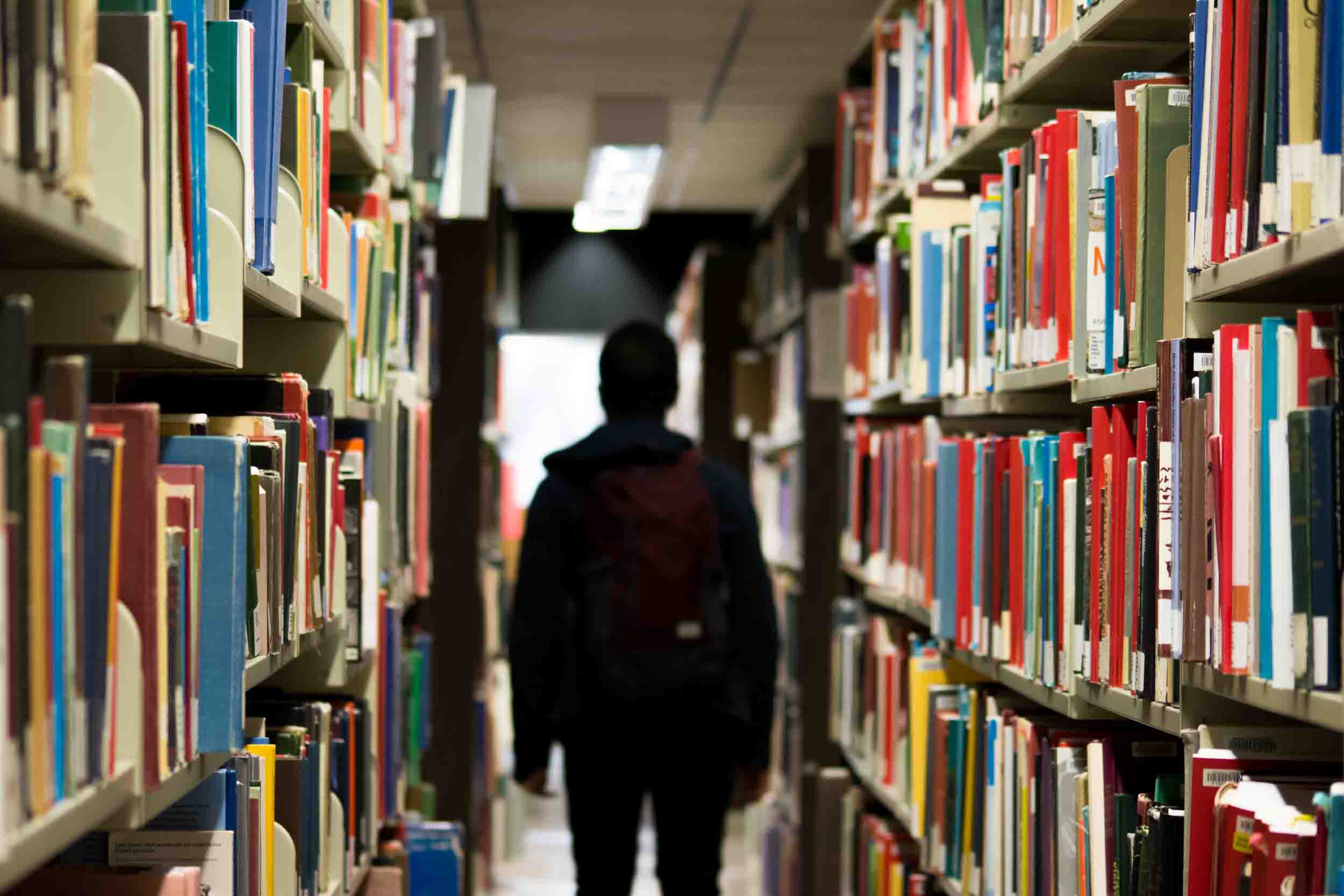

Title Image: Banter Snaps

This article, and everything from our magazines is best enjoyed in its magazine format. If you can’t get out to get your free copy, then check it out on issuu.com/risecollaborative. Or you can subscribe on our SHOP page and get it mailed to your door.

Written by Caitlin Hartney

‘Separate but equal’ is business as usual in Buffalo and elsewhere. A regional solution could fix that.

The idea that separate is inherently unequal entered our collective consciousness in 1954. That year, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that racial segregation in public schools violates the fourteenth amendment. In the court’s unanimous opinion, even if schools’ “physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors” are equal,” the fact that they are segregated deprives minority children of equal education. Separateness, in and oregf itself, is unconstitutional.

By the 1990s, when I was in public school, “separate is inherently unequal” was instilled in me and my lily-white classmates with the same reverence as our inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. To be American, we were taught, is to uphold the essentialism that segregation, de jure or de facto, is wrong.

In practice, “separate is inherently unequal,” is more lofty rhetoric than governing rule. The reality is, untold numbers of schoolchildren are sitting in segregated classrooms—and suffering because of it.

That separateness assails minority children’s integrity, subjects them to worse learning environments than their white peers, and sustains the racial achievement gap, putting their livelihoods and our economy at risk. School segregation also harms white children and our social fabric. Exposure to cultures and circumstances other than our own nurtures empathy and emotional intelligence, making us better people, communicators, and citizens.

And yet, we’ve abandoned the desegregation efforts that characterized education reform in the second half of the twentieth century, back when federal courts, North and South, still enforced desegregation programs. When judges released districts from their mandates to integrate, we redrew the line between white and black, undoing much of the progress that had been made. Since then, we’ve focused education reform on equalizing separateness, forgetting that Brown insists it can never be so.

Such is the state of education in many American cities. But in few places is it playing out more dramatically than in Buffalo, the sixth most segregated metropolitan area in the country and among the nation’s poorest.

Buffalo Apartheid

When I asked Dr. Gary Orfield if all students in Buffalo have equal access to quality education, he sighed:

“Of course, they don’t. That’s true of almost every city, but Buffalo is especially racially polarized.”

Orfield is a professor and co-director of the Civil Rights Project at University of California, Los Angeles. He is also well acquainted with public education in Buffalo. In 2014, Orfield was hired by the district to study racial disparities in Buffalo Public Schools (BPS). The district hired Orfield following the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights’ ruling that Buffalo’s admissions-based schools—particularly it’s best schools, City Honors and Olmsted Elementary—employ discriminatory practices that disproportionately exclude non-white students.

In the five years since, the inaccessibility of City Honors has only worsened for black students. When Orfield first arrived in Buffalo, 20 percent of City Honors students were black. In 2019, that number fell to just over 16 percent, despite the fact that black students comprise 46 percent of students in the district. The majority of City Honors students—59 percent—are white. In contrast, white children account for just 20 percent of total district enrollment.

But City Honors is just one, albeit emblematic part of a much bigger problem that began and continues to be fueled at the regional level.

A Legacy of Segregation

In the 1930s, the federal government took the official position that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities,” adopting policies like redlining in cities like Buffalo to explicitly force residential segregation.

Working with private companies, the government refused to provide financial services for properties in and near black neighborhoods. It also structured loans to make it easier for white people to buy a new house in the suburbs rather than improve an old one in the city, and it subsidized suburban housing developments on the condition that they disallow black homebuyers, among other reprehensible initiatives.

In effect, the government catalyzed disinvestment in cities and aided and abetted “white flight.” In 1950, white residents made up 93.5 percent of Buffalo’s population; by 1973, the proportion of white residents had dropped to 54 percent. Today, it stands at 44 percent.

When white people withdrew, they took with them their resources and political clout, enriching suburban districts at the expense of city schools and the minority children held in bondage by state-sanctioned segregationist policies.

That legacy mars the Buffalo metropolitan area to this day, with most white residents concentrated in affluent suburbs and select, racially isolated urban neighborhoods west of Main Street and south of downtown. Last year, 80 percent of BPS students were non-white and 82 percent were economically disadvantaged. Compare that to Kenmore-Town of Tonawanda, where non-white and economically disadvantaged students comprise just 23 and 44 percent of the student body, respectively. In the Amherst Central School District, it’s 30 and 31 percent; In East Aurora, it’s a mere 5 and 16.

Undoubtedly, the vestiges of redlining are still with us, and every time a middle-class white family moves out of the city “for better schools,” or pays for a parochial education rather than risk not getting into Olmsted, or an urban landlord denies a Section 8 housing voucher in an up-and-coming Buffalo neighborhood, or a city-wide tax reassessment drives people of color from their homes, the legacy perpetuates.

And it’s not just segregation by race. The Buffalo metropolitan area is doubly segregated by socioeconomic status. In our country, race and class often correlate, thanks to systemic racism that disproportionately entraps people of color in poverty, making it difficult to untangle the parallel forms of segregation in our community.

In effect, white, affluent children and minority, economically disadvantaged children are largely isolated from one another, with the latter relegated to under-resourced schools that consistently fail to meet state standards. This year, upward of 40 Buffalo schools meet the criteria for racial segregation, defined as at least 80 percent minority. Of those, at least 20 schools are considered “intensely segregated,” meaning the percentage of white students does not exceed 10 percent.

Segregation’s Implications

Given the extreme racial and socioeconomic isolation in the Buffalo metropolitan area, it should come as no surprise that Buffalo schools continue to underperform. Studies show minority segregated schools are more likely to have less resources, less qualified teachers, worse facilities, and little to no access to rigorous course offerings like Advanced Placement classes.

What’s more, concentrated poverty makes it difficult for a child who is already behind to realize his or her potential. Children living in poverty often come from high-stress households, where guardians struggle to meet their basic needs. They live in food deserts, throttling their access to good nutrition. They experience higher rates of trauma from violence, and they are commonly exposed to toxins—like the lead paint prevalent in Buffalo’s poorest zip codes—that hinder healthy development. As New York Times reporter Nikole Hannah Jones explained in an episode of This American Life, extreme hardships amassed in a single environment make getting ahead next to impossible.

“If you’re surrounded by a bunch of kids who are all behind, you stay behind,” she said. “But if you’re in a classroom that has some kids behind and some kids advanced, the kids who are behind tend to catch up.”

The mechanism at play, she points out, isn’t magic.

“It’s not that suddenly a switch turns on and they get intelligence or wanting the desire to learn when they’re with white kids. What integration does is it gets black kids in the same facilities as white kids, and therefore it gets them access to the same things that those kids get.”

Separate and Tangibly Unequal

Just by nature of being separate, then, thousands of Buffalo schoolchildren are being denied their constitutional right to equal education. Compounding that injustice is the fact that the separateness isn’t just conceptual, it’s also tangibly unequal, especially in comparison to suburban schools.

Interdistrict disparity is a concern of Larry Scott, who has two children enrolled in BPS. Scott is also a school psychologist for Kenmore-Tonawanda and a newly elected member of the Buffalo Board of Education.

“Over the past few years, I believe that the district and Board of Education have been very intentional in trying to provide equity across the system,” he said. “My concern is the inequity compared to what our suburban students receive. Working in a suburban district, I know firsthand that BPS is significantly understaffed for reading and math specialists, mental health professionals, librarians, art, music, and technology. Our Buffalo students also deserve increased access to Advanced Placement and accelerated programming.”

Better Together

Despite the observable interdistrict disparities and their questionable constitutionality, desegregation as a means of education reform isn’t just off the table; it’s in another room. That neglects not only our American values but also the decades of research that indicate minority children’s outcomes are notably better when, by sharing classrooms with white, middle-class students, they gain access to their same resources.

Most famously, desegregation has been associated with significant test score improvements. From the time desegregation efforts began in earnest on a national scale in 1971 through the peak of desegregation in 1988, the reading test score gap between white and black children was cut nearly in half—the most dramatic narrowing ever recorded, according to Orfield. As desegregation programs were dismantled through the 1990s, the gap reopened.

Studies also show that minority students who attended court-ordered integrated schools were in better health and less likely to struggle financially as adults than those who did not. Integration also seems to better prepare students for success in college, and it lends students of both races bicultural fluency that serves them later in life, as employees and as citizens.

“The very positive thing about the research on integration is that the disadvantaged kids gain, and the more privileged kids lose nothing, and everyone wins in terms of understanding and interacting more effectively,” Orfield said. “It’s not a zero-sum game.”

Brown on the Backburner

In place of integration initiatives, officials, philanthropists, and activists in Buffalo are focusing their efforts on improving the quality of schools in their segregated condition. “Separate but equal” is the unspoken name of the game.

In some ways, they are making measurable progress. This year, 46 of 60 Buffalo schools are in good standing with New York State. That’s up from just 15 schools three years ago. And only three schools are in receivership (at risk of closing due to poor performance) compared to 25 schools in 2015. Standardized test scores have also increased. In 2019, 25 percent of Buffalo students were proficient in reading, compared to just 16 percent in 2016. The most lauded improvement, though, is the graduation rate, which today stands at 65 percent—a 16-year high for the district.

Ask stakeholders what’s driving the progress, and they’ll credit increased parent involvement, a determined superintendent, and the creation of 23 Strong Community Schools across the district. Community Schools offer extended-day and extended-year programming and enrichment activities for children and adults to reduce learning gaps and strengthen parent and community engagement. Community Schools also work with Say Yes Buffalo and corporate partners to offer medical, dental, and wellness services to students, their families, and the neighborhood.

According to Clotilde Perez-Bode Dedecker, president and CEO of the Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo and Say Yes board member, 65,000 people attended Saturday enrichment sessions at Community Schools last year. Scott calls the initiative “a game changer” in addressing inequity and improving educational and future outcomes for Buffalo students.

Behind the Numbers

Jessica Bauer Walker, executive director of the Community Health Worker Network of Buffalo and a dogged BPS parent advocate, celebrates the progress made in recent years and praises the access Community Schools have provided. In her experience, there are “incredible educational experiences” to be had in BPS, but she concedes that access to high-equality education in Buffalo is not equitable. She points to her frequent battles like having to beg and fight for funding, fresh food, mental health resources, and physical education for her children’s school. It worries her that other parents in Buffalo are not as well positioned as she is to speak out for their kids.

“It feels like an oppressive situation, a lot of times, for parents who can’t fight back,” she said. “Most don’t have the time or resources. Parents are working multiple jobs or navigating public assistance and have lots of other types of issues. Not everyone can go into the school and call the teacher and push through the barriers. Parents that have two-parent households, speak English, and have resources and jobs that allow for time off are much better positioned to get what they need for their children.”

Bauer Walker also questions the efficacy of some of the measurements used to track the district’s progress:

“We’re measuring graduation rates. We’re measuring test scores. But what are the equity indicators; how are we measuring those? Even with Community Schools, we’re measuring the number of people coming in, but what’s the quality of the engagement?”

To her point, despite the district’s upswing, 15 schools are still in poor standing, and 75 percent of students tested this past spring—3,290 living, breathing humans—cannot read at grade level. That’s enough children to fill a not-so-small suburban district.

Moreover, the improved graduation rates veil the fact that about half of the BPS high school graduates who continue their education on a Say Yes scholarship drop out before they finish a post-secondary program, with signs pointing to ill-preparation as a leading cause.

The Irony of It All

BPS was once a model of purposeful desegregation. In 1976, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of New York determined that Buffalo had violated minority children’s fourteenth amendment rights by intentionally causing and maintaining a segregated school system. For the next 20 years, the district was subject to a court-ordered integration plan requiring schools be made up of 30 to 65 percent non-white students. That plan included busing and the creation of highly appealing, academically challenging magnet schools, one of which was City Honors. The magnet schools were attractive to Buffalo families of all races, cultures, and backgrounds but were held to certain enrollment quotas to ensure balanced diversity.

In 1995, Judge John Curtin lifted the order. Soon after, the admissions processes at high-performing schools like City Honors were retooled to favor white students; quotas were dropped, and resegregation eventually prevailed across the district.

What came to pass is an education system that, in some ways, isn’t more equitable than in it was in 1976 when Curtin ruled it unconstitutional. A primary difference between then and now is the resolve of the government to correct the problem.

A Path Forward?

Articulating his original decision, Curtin stated that the problem of segregation is difficult and will require rigorous effort to overcome, but “overcome it we must.” Stakeholders in 2019 appear to agree with the logic that racially and socioeconomically balanced educational environments are valuable to our city.

“Having an inclusive school system is best for everyone, and the more diversity you have, the more likely you can create an inclusive experience,” said Perez-Bode Dedecker. “So, we have to undo a lot of the structures and institutional policies that created the segregation. Intentional work has to happen because it was intentional work that created this.”

It’s coming to a consensus on the what and how of that intentional work that’s difficult.

Forced busing—effective as it was at integrating schools and reducing the achievement gap—has been so thoroughly demonized by white mothers insistent on preserving the racial purity of their children’s classrooms that it has been rendered political inexpedient. Moreover, while many people of color support integration, many don’t consider forced busing—a solution fraught with various stressors and animosities—the best means of achieving that end. In its place, we might take inspiration from other cities that have devised alternative integration solutions.

For the past 55 years, New York’s Monroe County has employed the Urban-Suburban Inter-district Transfer Program to “decrease racial isolation, deconcentrate poverty, and enhance opportunities for students in the Rochester City School District and in the suburban districts of the Greater Rochester Area.” The program is voluntary in two directions: it allows minority city students unhappy with their city education to fill open spots at 15 self-elected suburban school districts. According to Sam Radford, president of the BPS District Parent Coordinating Council, not to long ago, his group engaged suburban districts in talks to start a similar program in the Western New York, but the initiative fell through when the districts couldn’t agree on terms.

Other metro areas, including some in Connecticut, rely on regional magnet schools so academically appealing that parents from urban and suburban communities alike are eager to send their children, creating a mutually beneficial solution to the challenge of diversified enrollment. Among the litany of recommendations Orfield made to BPS following his 2014 study was a regional magnet school operated in partnership with the University of Buffalo. That recommendation, along with others deemed difficult or unproven by the school board, never materialized.

The programs in Rochester and Connecticut don’t solve the problem of segregation for every student, but they are a starting point. Bright spots like these give credence to the hope that one day we can arrive at a comprehensive, boundary-breaking solution to mitigate the effects of segregation in ways that wide swaths of the community will support

Not that everyone agrees a regional solution is the best solution. Radford favors neighborhood schools that keep parents close to their children’s education, fostering whole-household and whole-community participation in a student’s academic success. To address the inequity currently undermining some of BPS’s neighborhood schools, he suggests instituting a teacher residency requirement:

“I personally believe if you have teachers with skin in the game—if their children are enrolled where they teach—they will make sure those kids learn.”

That said, he admits a regional solution would benefit everyone and be worth the struggle. He is also certain many BPS parents would embrace the idea.

“Every parent I know wants better for their child,” he said. “And wherever better is, they are going to go.”

A Democratic Imperative

When Curtin first ordered Buffalo’s desegregation, he made a point of stating that the law does not prohibit “a metro response to what is essentially a metropolitan problem” and instructed the state to investigate a plan that would encompass suburban districts on a voluntary basis.

In 40 years, nothing has come of Curtin’s request, but is it not our moral duty and in everyone’s best interest to work collectively toward a solution—to ask how we can help, even if we don’t have a child in Buffalo schools? Every year that we don’t, hundreds if not thousands of students—each one of them as important as the children within your arbitrarily drawn suburban district boundaries—are at risk of being lost to a system that does not nurture their intrinsic potential.

If that’s not enough, consider the fate of our community. With more than 30,000 children enrolled, BPS is the largest school district in the area, which means the economic health of our entire region is largely dependent on the success of its students. If we create opportunities for inter-district collaboration, and if more white, middle-class parents were more willing to work with and less eager to flee BPS, we could amplify the admirable work being done in Buffalo at the neighborhood level—and live up to our democratic ideals in the process.