“The Unfinished Sexual Revolution” is an article that was released May 10 in Rise’s magazine, No Boundaries.

We must insist that the best way to enjoy it is by picking up your own free copy, still available at many shops around the city and suburbs.

Unable to get out? You can subscribe and we’ll mail it to you.

Still wanna see it in its entirety RIGHT NOW? Click here for full view on ISSUU, or read it here broken down for our blog.

What goes into stopping people in their tracks with an article?

Caitlin Hartney submitted her third article to No Boundaries in this spring’s issue. Having previously focused on women’s empowerment and the justice or injustice behind our city and country’s collective recollection of historical figures and events, Hartney produced her strongest piece to date with “The Unfinished Sexual Revolution.”

In Fall 2018’s 4th edition of NB, local designer and professor at Daemen College Casey Kelly joined our production to lay out the design for our article covering the affect opiates have had on three different friends, neighbors, families quite like yours and mine (version on ISSUU coming soon). Kelly returned for Issue 5 to team up with Hartney while this article was in development.

We’ve asked both women to comment on their process, the inspiration and meaning behind their work here.

Designer Casey Kelly

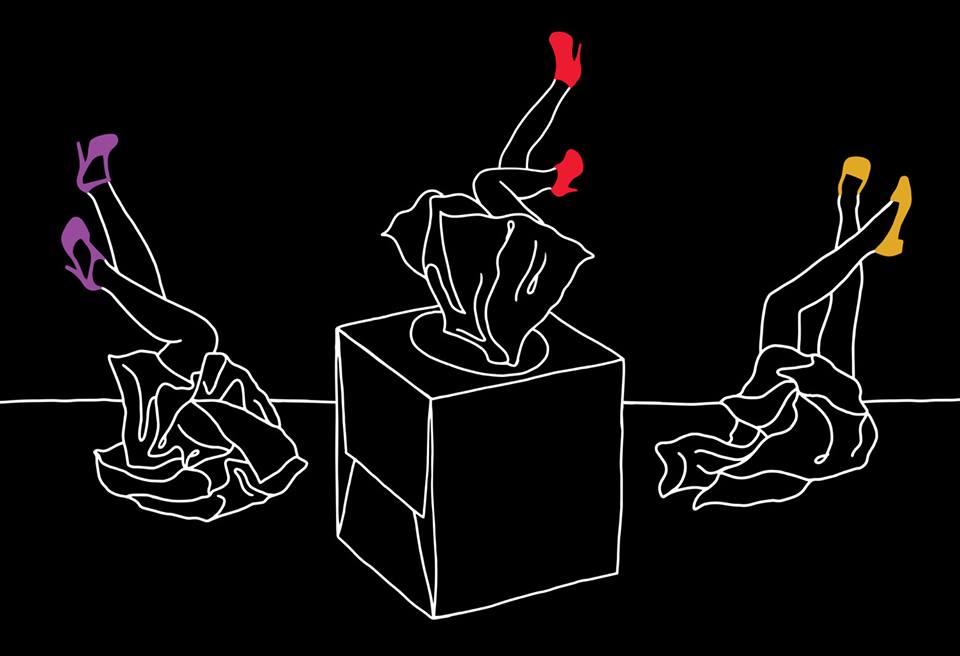

Make it look good? This is often what a lot of people first ask and think that the job of a graphic designer entails. I agree, but aesthetics are often just the point of entry. What someone might qualify as ‘good’ design is most often a result of the emotion provoked from consuming information in a form that is best fit for the content. There is thought and idea behind it. Design serves to communicate an idea.

Author Caitlin Hartney

The impetus for this article started way back in 2017, when the clamor surrounding the Aziz Ansari exposé came to a head. In the aftermath of that controversy, a dialogue opened up within the larger #MeToo movement about all of the everyday, commonplace bad experiences women had around sex—and by that I mean all of the bad experiences separate from assault and harassment.

Of course, it was no secret that women have long been subject to mistreatment and objectification in the bedroom and the locker room. It has been the fodder of comedy for decades. But for the first time, at least in my lifetime, it felt like the tone of the conversation had shifted from one of a “that’s life/boys will be boys” acceptance of the state of our sexual culture to a tone suffused with loud, tangible anger and resentment. The pain behind the mistreatment was really palpable in a big, public way. For me, personally, that felt justifying. It made it clear that I was not alone, and my girlfriends were not alone, in the negative feelings we had accumulated around sex. We were not isolated, and our feelings were not “crazy.” Realizing that you are not alone in your experiences or emotions and hearing people put words to the stormy thoughts and anxieties inside of you is really liberating.

But it was also much bigger than that. As I started paying attention to the cultural conversations around this topic, I was almost immediately reminded of a book I had read as a graduate student in the history program at UB. Ruth Rosen is a vanguard historian of gender and society, and in her book The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America, she dedicates an entire chapter to what she calls the hidden injuries of sex. In it, she chronicles how women in the 1960s and 70s felt about the liberal sexual culture that was opening up around them, and I remember realizing that the hurt and anger I was hearing in women’s stories in 2017 were practically identical to the feelings feminists were expressing four decades ago. And that’s when I realized that a larger social phenomenon was at play—that this wasn’t just about a couple women who found themselves in bad situations. It was about a broken sexual culture, designed and long controlled by men, in which women are conditioned to need sexual attention from men for validation. They feel pressure internally and externally to surrender their power to get it, and men take advantage of that, consciously or not.

And so I wrote this article to draw attention to the legacy of mistreatment undergirding our anger, and I wanted to provide a rebuttal to critics who deride women’s anger around their personal experiences of bad sex. For feminists, the personal has always been political. It has had to be, because women’s identities are so connected to their bodily autonomy and also because women’s power has, systemically and historically, been tied to the domestic sphere.

In any case, I think our is a sexual culture ripe for change. Which is not to say that sex can’t be amazing! It definitely can be and often is. But enough of it is bad to warrant a reevaluation of how we think and talk about casual sex. And it really all starts with doing a better job of being honest with ourselves and each other about what it is we really need and want out of sex and our sexual relationships.