Written by Tyler Bagwell

Edited by Sydney Pfeifer

Title Image by Kevin Heffernan

—Excerpt from Charles Baudelaire’s 1857 poem Le Voyage:

O the poor lover of imaginary lands!

Must he be put in irons, thrown into the sea,

That drunken sailor, inventor of Americas,

Whose mirage makes the abyss more bitter?

Early in the morning on Friday, July 10, the Federation of Italian Societies reclaimed the statue of Christopher Columbus it had donated to the City of Buffalo in 1952. “We are here today not to remove Columbus but to relocate him to a different place” former Federation President Don Allesi said at a press conference on the day the statue was removed from its plinth on Porter Avenue. The press conference, which featured speeches from Mayor Byron Brown, City Council members Feroleto and Rivera never once mentioned indigenous people until prompted by a reporter during Q & A.

This comes after statues of the explorer nationwide have been vandalized, torn down, and sunk. Allesi named “Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Orleans, San Francisco, there’s a litany of cities which have suffered violence and destruction of their Columbus statues and we were not going to let that happen in our city.”

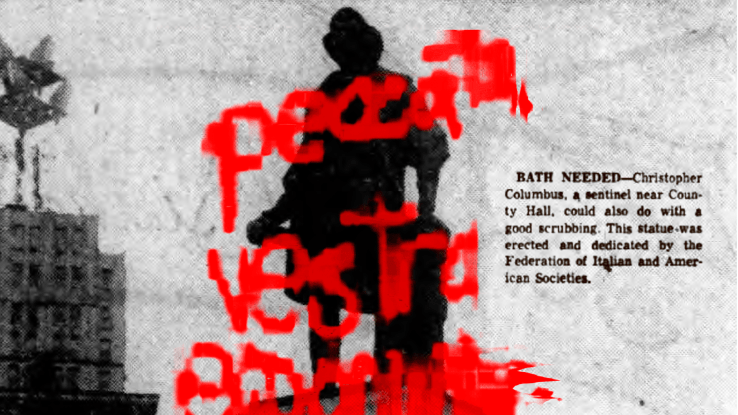

Only four days prior, Buffalo’s statue had been vandalized– the most recent in a long line of these occurrences.

In 2018 red paint was dispatched in illegible scrawls.

In 2017 red paint dripped down the navigator’s legs.

In 2016 “Columbus was a slaver and a rapist,” in green chalk. A black garbage bag over the statue’s head.

In 2015 “Genocide,” and “slaver,” in black. In red “rape,” and “peccata vestra exponuntur,” latin for “your sins are exposed.”

In 1975 star spangled bunting made for a blindfold.

As our country struggles with the sins of slavery and colonialism it has spurred an evaluation of our history and the monuments to it. The debate over Columbus illustrates a divide in public opinion. For Italian Americans, Columbus has been an invaluable symbol of their heritage. On the other side, Columbus is chastised as “The Patron Saint of Colonial Violence.”

As the statue comes down, it’s worth exploring this contrast. How did the image of Columbus become a symbol of oppression when the image itself was nurtured by Italian Americans struggling against oppression of their own? The case of Columbus as a symbol speaks deeply to the complexity of American Identity.

The symbol of Columbus was the result of tireless campaigning by generations of Italian Americans searching for representation in our national mythology. But that’s exactly what we ended up with- a myth and a symbol.

Italian Americans did not create the fiction of Columbus, however. That was American writer Washington Irving, of Sleepy Hollow fame, who, in 1828, wrote a highly fictionalized biography of Columbus which served as the foundation of his veneration, but did not alone make Columbus a saint. Columbus was foisted into the firmament as a defense mechanism against the rampant anti-catholicism of the 19th century.

In 1882 Father Michael J. McGivney, the child of Irish immigrants, invoked the sailor’s name in the founding of the Knights of Columbus as a fraternal organization to support working class Catholic Americans. In 1876, Father Antonio Isoleri, serving at the United States’ first Italian Catholic church in Philadelphia, arranged to have a statue erected in that city. It stands as one of the country’s oldest Columbus statues.

The final incident solidifying Columbus’ canonization came in 1891 when eleven Italian-Americans were lynched in New Orleans. What followed was great tension between the governments of the United States and Italy. Both countries removed ambassadors from the other, and Italy demanded the lynch mob arrested and reparations paid. Diplomatic relations were at a stand-still for a year until President Benjamin Harrison went over congress to pay $2,211.90 indemnity to the victims’ families and in 1892 declared the first nationwide celebration of Columbus Day in an attempt to pander to Italian Americans. Columbus Day would from there gain popularity on a state by state basis, but to become a federal holiday it would take a lifetime of campaigning by Italian Americans. Which brings us back to Buffalo.

Mariana Lucca was born in 1901 in the Italian neighborhood known as Dante Place, now Canalside. Among his claims to fame are in utero attendance of the assassination of President William McKinley and a fantastic anecdote about him refusing to lower his eyes to Mousillini.

Lucca’s crown achievement was founding the National Columbus Day Committee which lobbied congress to make it a federal holiday, which it finally did in 1968.

Buffalo’s Columbus Statue too was a lifetime of work by Buffalo’s Italian American community.

On Columbus day 1952 a statue of Columbus by sculptor Giovani Polizzi was unveiled on a triangle of land formed by Niagara, Franklin, and Mowhak.

The Federation of Italian American Societies raised the $16,000 for the 7 foot statue over a period of 40 years. An earlier proposal for an 18 foot sculpture by James Novelli, at an estimated cost of $25,000, ran into problems with funding and location and was scrapped in the 1930s. Finally, with funds in place, the City of Buffalo donated the triangle on Franklin and Niagara where the statue stood for 17 years until urban renewal displaced it. In 1969, Columbus journeyed at a cost of $1,500 to its current location in Columbus neé Prospect Park.

This brief history of Buffalo’s Columbus statue puts perspective on how brief his prominence has been. He has only been important to Americans for the past century, and only because Italian Americans willed that importance into existence.

Columbus’ mid century admiration was called into question almost immediately. Columbus Day as a federal holiday had been in place for less than a decade before Indiginous People’s Day was suggested as its replacement at a 1977 Geneva Convention. Howard Zinn’s 1980 A People’s History of the United States introduced two-million readers to the reality of Columbus that Indigenous people had always known; that Columbus was less of a hero and more of a genocidal rapist who enslaved the indiginous peoples who were already on the land he “discovered.”

(Zinn Education Project Documentary The Columbus Controversy featuring SUNY Buffalo Professor and Seneca Historian John Mohawk.)

In arguments against his importance, it’s barely worth mentioning that Columbus wasn’t even the first European to make it to North America. St. Brendan may have been scrawling Ogham script into West Virginian rocks sometime around 500, and Leif Erikson landed in Newfoundland in 1001.

What is undeniable about the legacy of Columbus is that he opened up “The New World” to Europe and all that followed in the violent colonization that created our modern world. While that fact was not commonly known by the people who erected the statue, it is known now by the people who continue to hold onto the symbol of Columbus. And Don Allesi illustrated this divide at the press conference.

“Columbus in general…is symbolic not so much of the sailor from Genoa who sailed for Spain, but more importantly for the contributions made by Italian Americans to this country.”

Young Italian and Sicilian Buffalonians take this further in a statement released by community organization Ciao Bella. Andrew Delmonte is quoted: “The pride I feel for my family and our heritage has nothing to do with the murderer, colonizer, and rapist Christopher Columbus.”

Which begs a simple question: if it’s just a symbol, why not choose a new one?

Rise content is sponsored by Daemen College: