Written by Tyler Bagwell

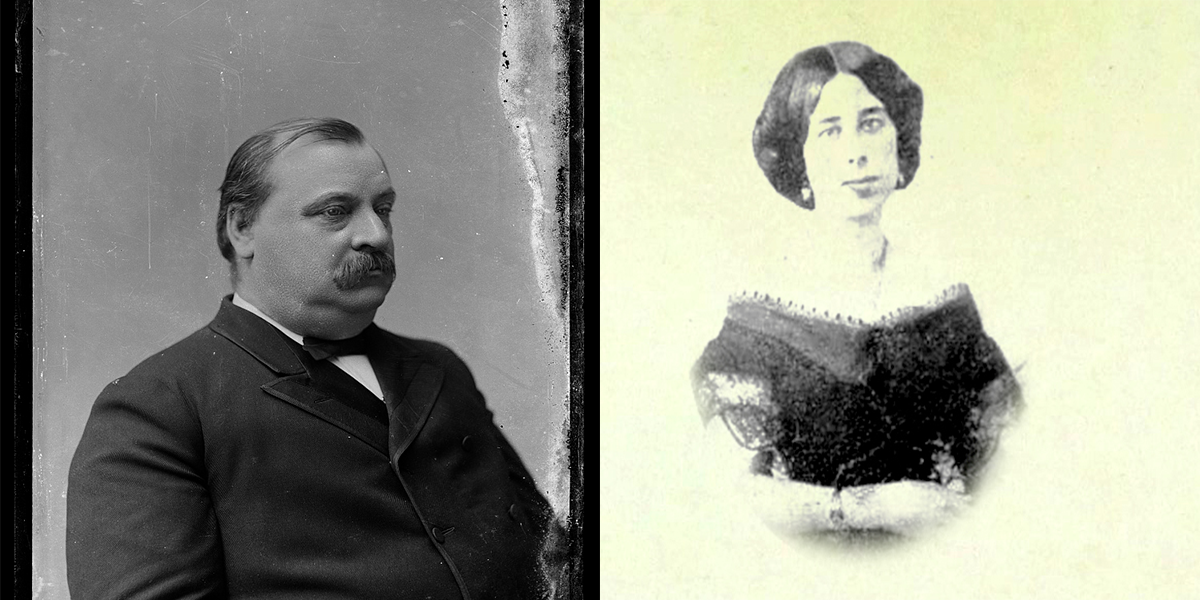

Maria Halpin didn’t report because her assailant was the sheriff and he told her “he was determined to secure [her] ruin if it cost him $10,000, or if he was hanged by the neck for it.” Also, it was 1873, and laws protecting women against sexual assault were nonexistent. When she did come forward in 1884, it was only to straighten out the stories printed about her and her assailant, Grover Cleveland, as he was campaigning to be president of the United States.

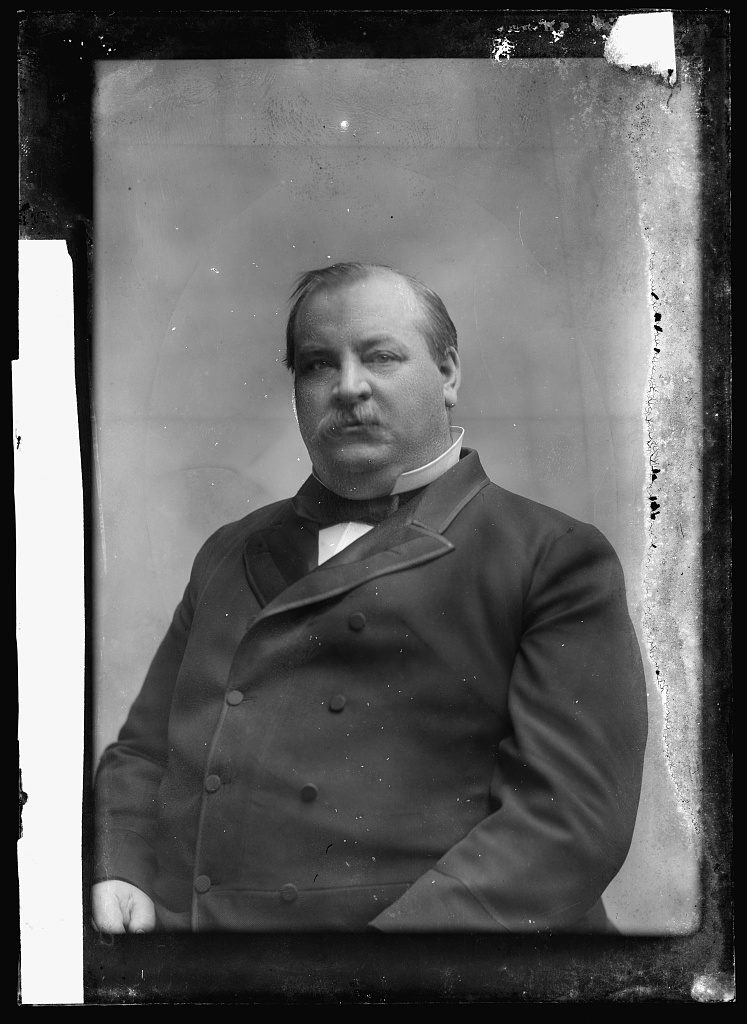

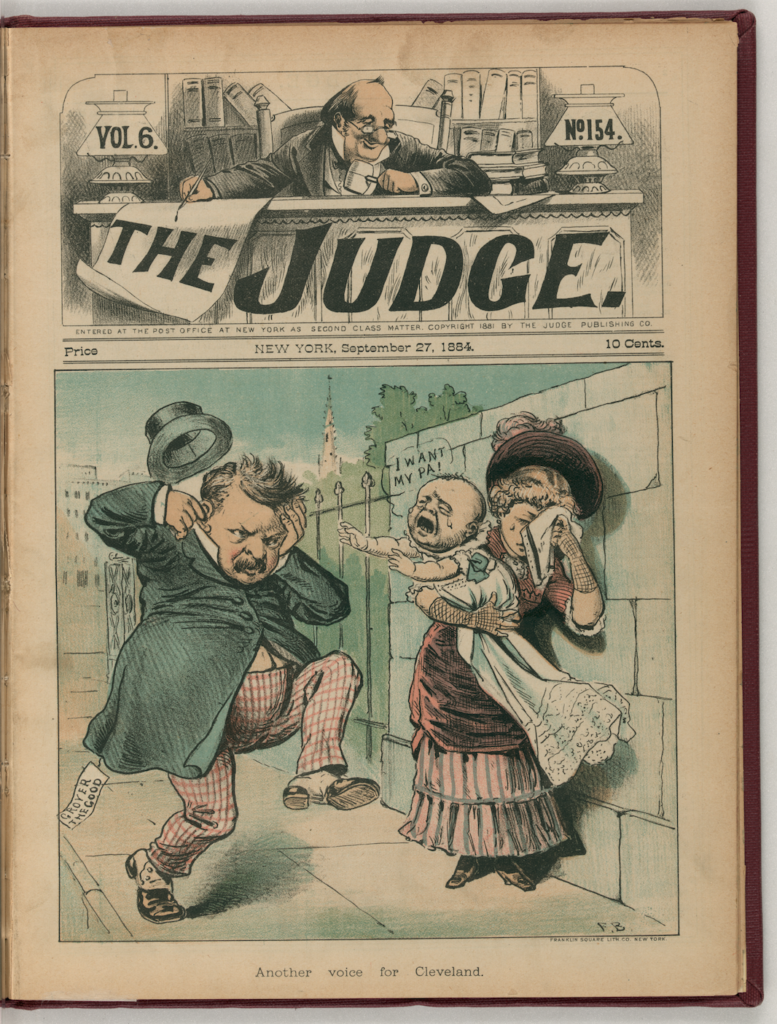

The election of 1884 between Cleveland, then governor of New York, and Secretary of State James Blaine was prone to the muckraking typical of any political contest. On July 21 of that year, the Buffalo Evening Telegraph ran a letter detailing alleged improprieties of its favorite adopted son. Cleveland was well known Buffalo for his meteoric climb from prominent lawyer to sheriff to mayor before winning the governorship of New York.

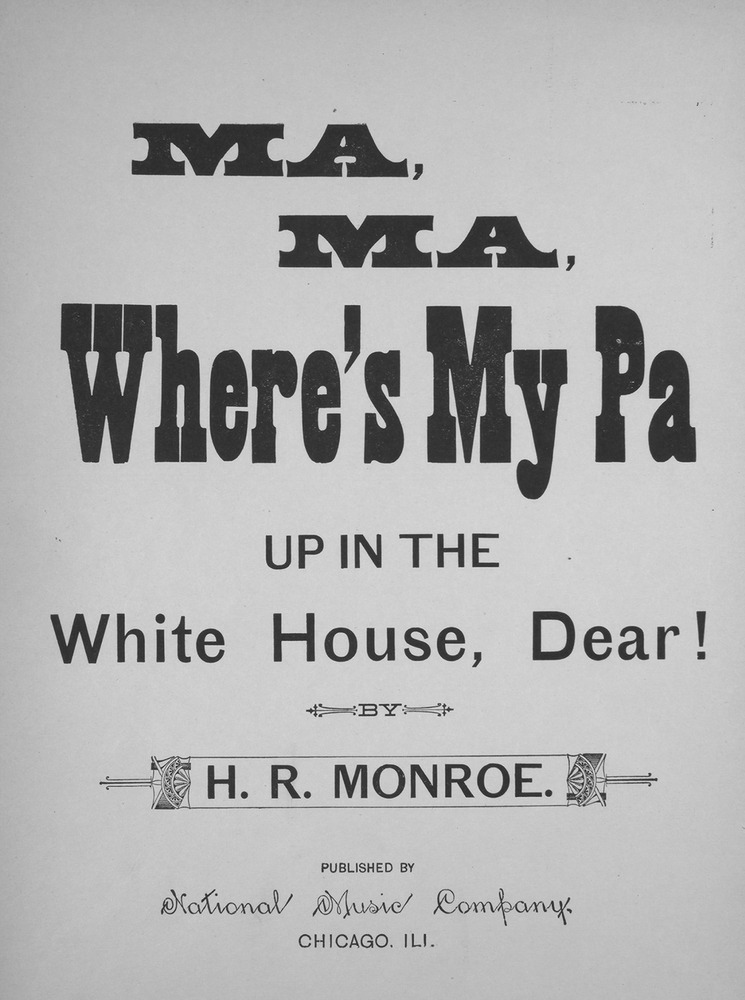

The letter, written by Reverend George Ball, portrayed Cleveland as a “beastly drunk” who had “habitual immoralities with women.” It contained dark descriptions of blood-soaked naked bar fights and all-night Sunday liquor parties where Cleveland and his friends called for lewd women. The most striking allegation staked that Cleveland had fathered a child out of wedlock with a Buffalo widow named Maria Halpin and used his authority to have her committed to an insane asylum and the child taken out of her custody.

Prominent men rushed to Cleveland’s defense. A letter published July 29 from an anonymous Republican lawyer claimed he “never saw him drunk,” and that Cleveland was never “distinguished in this city for licentiousness or debauchery.” Lewis Falley Allen echoed when asked if he knew his nephew to be drunk. “Never; I have never seen him so. He takes his glass of beer when he’s thirsty, but I guess he keeps his head about him all the time.”

The Telegraph’s accounts of drunken bar fights and liquor fueled parties were handily denied by Cleveland’s campaign. Furthermore Rev. Ball was more or less discredited. In spite of all this, Maria Halpin and her child could not be talked away.

A child had in fact been born to Maria Halpin on September 14, 1874. The child was given the name Oscar Folsom, at Cleveland’s behest. Cleveland took responsibility for the child’s support but maintained denial that he was the father.

Cleveland’s friends told reporters that “Grover Cleveland was one of a party of three gentleman who shared her intimacy, and that the child whom he consented to father, belonged in truth, to a married member of this trio of libertines.” The libertine in question was the child’s namesake, the late Oscar Folsom, Cleveland’s best friend and business partner.

In conjunction with Cleveland’s defense was the public defamation of Maria Halpin’s character. The press made no hesitation in branding her a “vile creature, a drunkard, a blackmailer, a perjurer, a would be murderess of her own offspring, a victim of delirium tremens, a proper inmate for a lunatic asylum, etc.”

Maria Halpin did in fact go to the Providence Lunatic Asylum, but the circumstances were complicated. Those close to Halpin confirm that she took to drinking after being spurned by Cleveland and his defenders credit the drink for landing her in Providence. But there’s evidence to show that Halpin was about to take legal action against Cleveland and that he used her alcoholism as an excuse to make her go away. Halpin and Cleveland’s relationship ended with the child being adopted and Halpin, life in tatters, being paid to disappear.

Halpin stayed disappeared until October 28, 1884, when she reluctantly came forward to repudiate the rumors.“I would gladly avoid further publicity of this terrible misfortune if I could do so without appearing to admit the foul and false statements concerning my character.” Halpin defended her character and without much detail asserted that Cleveland fathered her child. “The circumstances under which my ruin was accomplished is too revolting on the part of Grover Cleveland to be made public,” she stated. But Halpin never wavers in her certainty of Cleveland being the only possible father. “There is not and never was a doubt as to the paternity of our child.”

When asked about being “compromised” by Oscar Folsom, Halpin categorically denied the rumor, claiming “I never spoke a word to that man in my life.”

After much back peddling, Cleveland accepted the paternity of the child, and the scandal was over, but lost in the scandal were the circumstances under which the conception took place.

The day after her first testimony, Halpin returned to the notary to deliver a full account of the event she first thought “too revolting on the part of Grover Cleveland to be made public.”

On the evening of December 15, 1873, Halpin was on her way to meet a friend when she ran into then-Sheriff Cleveland, whom she’d known for several months. He asked her to dinner. She declined. He persisted, and she obliged. They proceeded to the Ocean Dining Hall and Oyster House at 11 Swan street. After dinner they continued to 39 Swan Street, Mrs. Randall’s Boarding House, where Halpin resided with her son. “While in my rooms he accomplished my ruin by the use of force and violence and without my consent,” Halpin’s words from the sworn affidavit. Grover Cleveland raped her. A child was born. Cleveland took responsibility for the child, and the circumstances of the conception were entirely disregarded. Worse yet, Cleveland used the semblance of honesty and responsibility as a platform in which to garner popularity with voters.

“Whatever you do, tell the truth,” stands as one of Cleveland’s most notable quotes in spite of its origins in this appalling episode. Contemporary portraits paint Cleveland as a bastion of honesty in contrast to James Blaine’s corruption, and historians point to it as a crucial piece of his victory in the election. Halpin’s description of the disturbing event was ignored not only in 1884 and for years after. When Halpin died in 1902, historians were already assembling grand biographies of Cleveland that would erase her story completely. Worse yet, in the intervening 150 years, when historians did cover the subject, they painted the assault as a playful romp along the ascent of Buffalo’s favorite hangman. Most historians prop up the dubious paternity theory while others descend to painting Halpin as a prostitute.

Journalist Patricia Miller points to Allen Nevins’ Pulitzer Prize winning 1932 biography of Cleveland as the source of historical neglect. “Nevins never bothered to dig deeper because it was simply inconceivable to him that a man like Cleveland could have done such a thing,” Miller said. “Most people who research the story simply accept his version as fact and never bother to go back to primary sources.” Miller’s forthcoming book Bringing Down the Colonel contains one of the most succinct reportings of Halpin’s story and the surrounding culture that silenced her. “No one could be expected to take her word over a man like Cleveland–his position and power proved his rectitude. Maria literally didn’t have a voice–the New York Times never even mentioned her name.”

The template that served for Halpin’s silencing is still applied today. When a candidate for public office is credibly accused of sexual misconduct the accuser is discredited, the candidate receives the benefit of the doubt, the system moves on. It happened to Maria Halpin. It happened to Paula Jones. It happened to Donald Trump’s 22 accusers. It happened to Christine Blasey Ford. The following quote from a November 1884 edition of Jingo asks the same question we’ve been asking ourselves this week.

“We have heretofore boasted that this was a land of domestic virtue, a land of homes and families, a land where woman was honored above all other lands. How shall we longer make these boasts, if we choose Grover Cleveland to be the First American Citizen, the foremost exemplar of American manhood?”

Maria Halpin and Christine Blasey Ford did not come forward to make a name for themselves. They did not come forward on behalf of partisan politics. They did not come forward to seek criminal justice for the atrocities against them. They came forward on behalf of their country to speak on the character of men they witnessed in the darkest moments of their lives. They came forward to keep these men from powerful positions. They came forward and we ignored them. We did it 134 years ago. We’ve done it now.