Written By Tyler Bagwell

One could argue that the most important song on Rick James’ 1981 punk funk magnum opus Street Songs is neither hit single “Super Freak” nor “Give it to me Baby,” but rather the scathing indictment of police brutality that closes the first side.

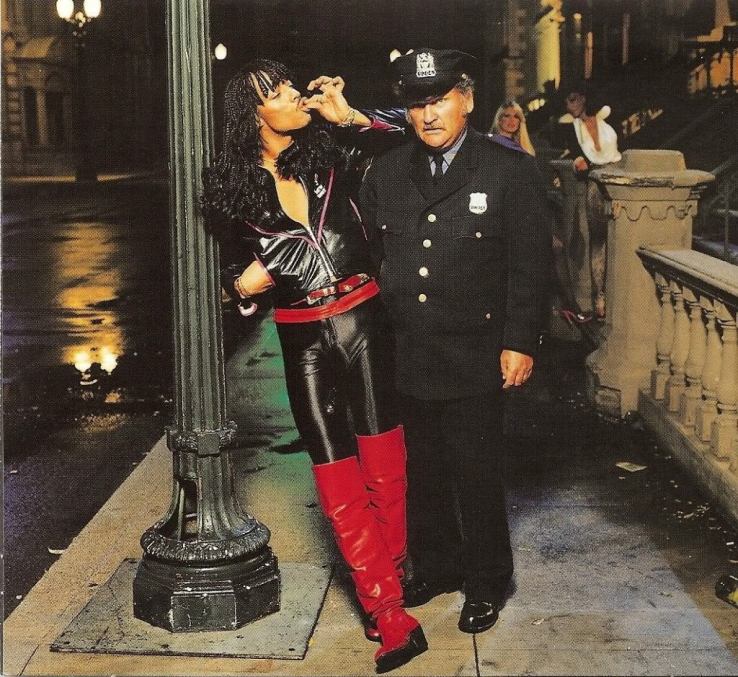

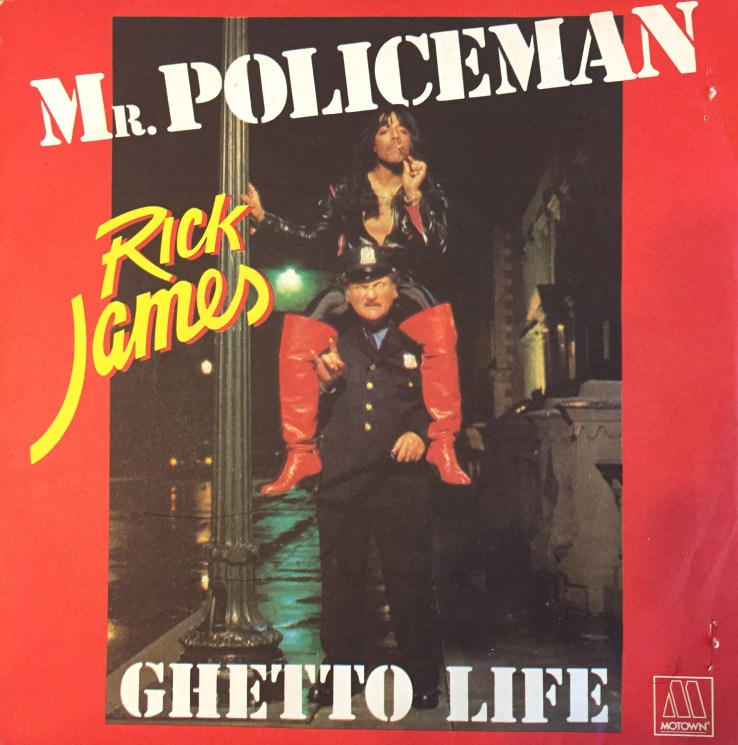

“There’s a song on there called ‘Mr. Policeman,’” Rick James told the Challenger in 1981, “which gives my feelings about the police. I think police brutality and police harassment are ridiculous and they need to be stopped.”

The song starts with a bassline reminiscent of 70s cop drama themes accompanied by the swirling siren of a Hammond B3. “I gave it a reggae flavor” James recalled in his memoir “because I had recently watched Jimmy Cliff’s The Harder They Come for the second time.” Like that 1972 film, James’ song is the story of a police shooting. James’ vocals dance between melodic and guttural as he howls “It’s a shame. It’s a disgrace. Why every time you show your face somebody dies.” The song is a document of a shared experience in Buffalo and cities nationwide in which minority communities were and continue to be subjugated by police violence.

Rick James’ 1981 studio version of “Mr. Policeman” from the Platinum album Street songs featuring Stevie Wonder on harmonica.

In Rick James’ own words “Mr. Policeman” is “the story of a friend gunned down in Buffalo by the cops.”

In an attempt to learn more about the reality that inspired the song I asked Rick James’ brother, longtime manager, and artist LeRoi Johnson.

“The reality is that’s the life that we led. Living in the neighborhoods we lived in you were going to have those experiences. Those interactions with police, which were never really that good. You were going to hear about people getting shot. Possibly sometimes see it.”

The archives of Buffalo’s Challenger and Criterion newspapers are filled with these interactions which give context to the reality of the song. The examples below barely scratch the surface.

Headline from the Criterion of March 26, 1955.

In 1963 Buffalo Bills running back and kicker Cookie Gilchrist was beaten by Buffalo Police over a traffic violation.

In 1966 Patrolman Edward B. Wisniewski Jr. was cleared after shooting a 16 year old boy who ran after being identified by an elderly woman as a purse snatcher.

In 1967 a riot spread from the Lakeview housing project on the West Side across town to Jefferson Ferry. Eyewitnesses cite “stick happy” police for inciting the unrest.

In 1970 Police received a report that a sniper had shot a passing patrol car on Sycamore. Police, allegedly, responded by entering a home and spraying a “caustic substance” on the residents; two adults and three children aged ten, two, and three months. No sniper was found. Following the attack the police refused to appear in a line-up.

In 1972 James Smith was enjoying an afternoon with his sons, aged 10 and 6, at their home on Archie Street when “suddenly an axe hit the front door sending a chunk of wood flying across the floor striking him on the right elbow. Bullets sprinkled the room” the Challenger reported. Fearing for their lives they moved to the kitchen in the back of the house. A dog, naturally protective, was shot but not killed. “Finally one policeman shouted ‘you got the wrong house. THE WRONG HOUSE!!!” The police at the scene were reported to have been in plain clothes with no badges.

Seeing the discrepancy between Buffalo’s black community weeklies, Challenger and Criterion, against the major dailies Evening News and Courier Express, on the topic of police brutality is disappointing if not expected. Which leads to the question of what impact “Mr. Policeman” has had in bringing attention to the problem.

LeRoi Johnson points out the work of Harvard Professor Marcyliena Morgan with the Hiphop Archive and Research Institute at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research. Morgan stresses hip hop’s history of shining a light on police brutality. Johnson adds that hip hop’s mainstream popularity brought police brutality into the consciousness of suburban white consumers who were buying these records. Where Johnson takes issue with Morgan’s argument is her statement “We can start with Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s 1982 song “The Message.”

“Let me point out to you that Grandmaster Flash came on tour with us” Johnson continues. “No doubt they listened to Mr. Policeman, because we performed it, and they no doubt were influenced by it. And now you have a Harvard Professor writing about their influence on the hip hop scene with their protest against policemen and they say nothing about us being out ahead of that.”

The influence wasn’t disregarded by everybody. In a 2007 interview with Wax Poetics Ice Cube said this:

“Street Songs is kind of like the first gangster record. I felt like he was talking to me. It was the most hard-core record you could get at the time. There wasn’t anything else that I could remember—maybe a couple of rap records was out—but as far as R&B, this was about as hard and on the edge as you could get.”

In that same interview Dr. Todd Boyd, professor of Critical Studies, USC School of Cinematic Arts, said “Street Songs is certainly a precursor to what would become Straight Outta Compton, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, Illmatic, no question.”

An explanation to the enduring influence of Street Songs and “Mr. Policeman” can be found in this statement by LeRoi Johnson; “I think it was more of a general expression of what was going on in the period, which is no different than what’s going on now.”

The sad reality is that “Mr. Policeman” is just as relevant in present day Buffalo as it was when it was released in 1981 as it is to the midcentury of Rick James’ youth.

In recent memory Buffalo Police shot a man during a mental crisis call, A lawsuit is presently underway regarding a police beating that took place during a traffic stop, and a staggering 30 people have died while in custody at the Erie County Holding center since Sheriff Howard took office in 2005.

This reality is reflected still through music. Notably in Buffalo rapper Conway the Machine’s “Font Lines.” Inspired by the killing of George Floyd the 2020 song addresses the ongoing problem of “Cops killing black people on camera and don’t get charged.” In an interview with Donna-Claire Chesman for DJBooth, Conway said this:

“I’ve been a victim of police brutality and all that. Dirty-ass cops planting guns and drugs in the car, pulling you over for nothing. I’ve been beat by police a couple of times. Broken ribs, shit like that. My uncle died in police custody. I’m no stranger to it.”

In the same way you can draw a line from Rick James’ “Mr. Policeman” to Conway’s “Front Lines,” one too can draw a line from the brutality of the Buffalo Police Department of James’ adolescence to the present day. While Rick James was by no means the first black artist to sing about police brutality it is important to recognize his role in this tradition and the influence “Mr. Policeman” and Street Songs has had on the 40 years of music that has followed, and even more importantly the social consciousness that continues to evolve even when the police don’t.