By Ashera Buhite

There seemed to be a growing resentment amongst some of the local people. I cannot place when I first noticed that Lucy Fest and its attendees began to be treated as pariahs, but I knew there was growing discontent. Around the age of 17, I noticed “Lucy Was A Slut” stickers begin to appear around town. Weekly they would appear on the bench outside of the little museum, and a worker would calmly peel it off every week with Goo-Gone.

I got my first job at the Lucille Ball Desi Arnaz Center when I was 15. I only worked 10 or 15 hours per week, as my working papers directed. I wore my khakis and black tee shirt to school every week and was sometimes chided by my classmates, but I made a whopping $8 per hour—an unheard of wage amongst my friends working in fast food in 2005.

Working in the museum was my first exposure to the bizarre intersection of retail, travel, and fan worship. The summer was busier, culminating in two separate festivals, Lucy Fest and her birthday celebration. During the winter months, there were few visitors in the hilly WNY territory. This afforded me the opportunity to learn all about the chaotic, hard-pressed life of Lucille Ball as I slowly watched nearly every film that she made.

Lucy grew up in the tiny lake town of Celeron, just outside of Jamestown. Her mother sent her to acting school in New York City at the age of 14, partially to support her and partially to dissuade her interest in an older neighborhood boy. Being quiet and shy, Lucy did not do particularly well in acting school, but was determined to make a name for herself. She finally landed a modeling job with Hattie Carnegie, but none of the work seemed to last. Finding little success in New York, Lucy headed to Hollywood to pursue her dreams.

In Hollywood, Lucy slowly began building her career, small role by small role through the 30’s, and then becoming “Queen of the B’s” in the 1940’s. It was during this time that she met Desi Arnaz while working on Dance, Girl, Dance. It was love at first sight, and the couple eloped within a year.

Lucy caught a break in 1948 after being cast in the radio show, My Favorite Husband. Asked to develop the show for television, Lucy enlisted her husband, Desi Arnaz to assist her. CBS initially rejected their pilot, believing that the public would not respond favorably to a Cuban/American marriage. The two took their show on the road as a vaudeville act. After finding a successful formula for their comedy and proving that the American public could handle seeing a white woman married to a Cuban man, Desilu Studios was formed. This made Lucille Ball the first female film executive in history. On October 15th, 1951, I Love Lucy was finally put into syndication, launching Lucy and Desi into stardom.

Earning five Emmys in six seasons, I Love Lucy was groundbreaking on multiple levels. Teaming up with Karl Freund, Ball and Arnaz pioneered the three-camera system and use of a live studio audience, which has become standard operating procedure in the filming of sitcoms. The show quickly gained intense popularity, placing a spotlight on Lucy and Desi’s personal life. In 1952, Lucy became the first pregnant woman to appear on television. Deemed too edgy, the word “pregnant” was never used, but instead referred to as “expecting.” On November 14th, 1952, more people tuned into see Little Ricky’s birth than the inauguration of President Eiesenhower.

After 6 seasons, I Love Lucy came to an end, but Desilu studios kept producing hits. After years in showbiz, Lucy had developed a keen sense of what audiences wanted. She approved well-developed and high-quality shows such as Mission Impossible, The Untouchables, and Star Trek. Despite their many successes, Ball and Arnaz’s marriage was strained and they split in 1960. Lucy took over Desilu and became the first female studio head. She simultaneously starred on Broadway and worked in television and film that year. Lucy worked up until her death in 1989. She was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and TV Guide named her The Best Star of All Time.

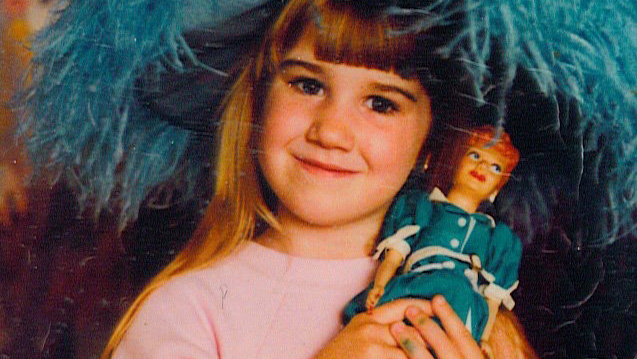

A few years after her death, my mother was involved with the creation of the Lucille Ball Desi Arnaz Center. Annually, the center hosted Lucy Fest, a weekend-long gathering of fans of the First Lady of Comedy. I remember the early ones through the eyes of childhood: there were rides in the street, a film festival, and Lucy impersonators. It felt big and important. The museum celebrated the innovations that Lucy had contributed and supported the work of up and coming comedians and filmmakers. It was something that I looked forward to each year.

Thank you to the Lexington Co-op with its location on Elmwood and new location on Hertel, for sponsoring No Boundaries!

Thank you to the Lexington Co-op with its location on Elmwood and new location on Hertel, for sponsoring No Boundaries!

Over time, Jamestown became increasingly covered in Lucy murals. They began springing up on many streets, all of famous I Love Lucy episodes—the chocolate factory, Vitameatavegamin, and California, Here We Come! As I grew into teenager-hood (and started working at the museum), I noticed that the festival was not what it once was. I didn’t see many locals anymore and there was no film festival. The fans themselves had also changed. There was less creative celebration of her, and they seemed less interested in her innovations and more into looping their favorite moments, over and over.

Instead of a film festival, people who had been periphery beings in Lucy’s life got on stage and regaled the audience with tidbits and memories. Lucy’s grave was moved to Jamestown’s Forest Lawn Cemetery, where people began placing “gifts” and letters on it. Interacting with the fans became sometimes unpleasant, as people yelled over Lucy-themed motorcycle jackets, tee-shirts, and cookie jars. I quit the following summer, disheartened by what I had seen.

That’s when the Lucy Was A Slut stickers started to appear. At the time, I saw them as an amusing troll on the people who flooded our streets one weekend a year. In hindsight, I recognize an undercurrent of misogyny in the sentiment asserting that a woman cannot be successful, attractive, and funny—she must have screwed her way to the top. Such allegations have been hurtled at plenty of female comedians.

After years of malcontent amongst the locals, something finally broke. The museum shifted its focus and began actively trying to be better than it was. Distilling the festival into one big celebration, bringing in top comedians, and reigniting the film festival has brought a resurgence to the area. The festival has broken two world records: the most Lucy Ricardos in one place, and largest grape stomp. Locals are participating in unprecedented amounts, and the Lucy Was A Slut stickers have dwindled into nonexistence. Could it be that 27 years after her death that Lucy and her hometown have finally come to a tentative peace?

I hope so, but there is much to be learned. Lucy’s life was full of complications and setbacks. To truly honor her legacy is to acknowledge the work she put into becoming the success she was. In that spirit, it’s imperative that future innovators like her are not ever reduced to a few key moments. Lucy was more than the chocolate factory and grape stomping scene. She was more than I Love Lucy. She, and innovators like her, are always more than the sum of their parts. Let’s embrace the entirety of her genius, complicated humanity.

Thank you, Kore Marketing, for your support of No Boundaries!

Thank you, Kore Marketing, for your support of No Boundaries!