Rise contributor Tyler Bagwell returns!!

The public, Pegulas, and Poloncarz conversate on the location of a new Bills stadium and all parties posit whether it should stay in Orchard Park yet little is said on why it’s there in the first place.

People have been talking about where to put a new stadium since forever. In 1954 the Buffalo Courier-Express asked readers “What Site Is Best For New Stadium?”

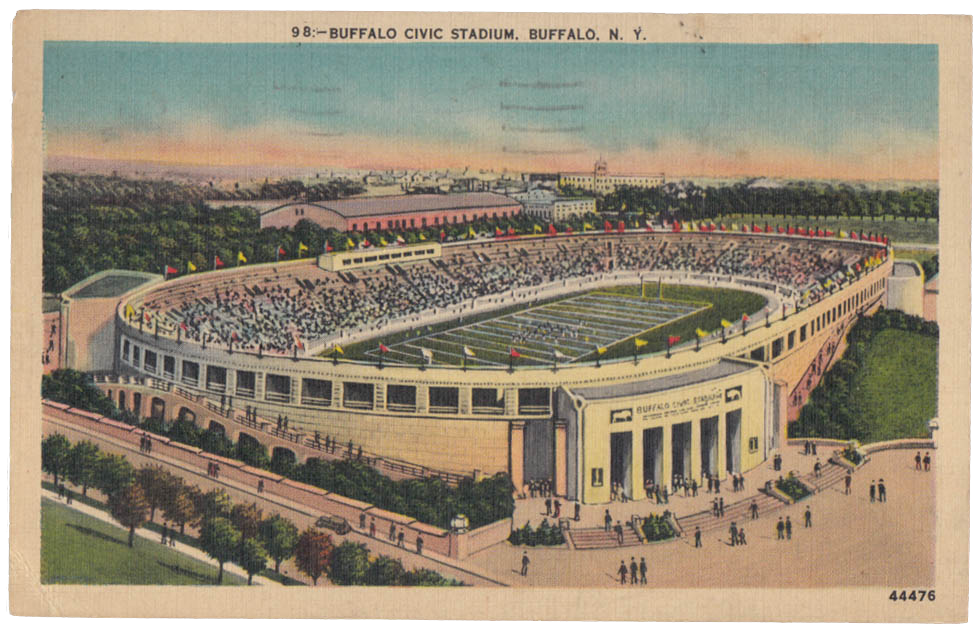

Arthur P. Deckert submitted “It should be located somewhere there is plenty of room for parking” and “in a central location easily accessible,” pointing to the Hill Street Quarry. This was 6 years before our Buffalo Bills would play their first game. In 1959 Ray Ryan wrote for the Courier-Express “Civic Stadium is a good place to watch a football game, once you have managed to get there and park your car. But it has a few drawbacks for the professional game” he wrote referring to the “36,000 odd permanent seats.”

The Buffalo Bills moved to Orchard Park as the consequence of numerous missteps between ownership and government that provided a last-resort solution instead of a good idea.

The road to Orchard Park is long and fraught. To understand how we got there you must first understand how the Buffalo Bills came into existence in the first place. For that there is no better place to start than 100 years ago with the “Staley Swindle.”

The Staley Swindle

The Buffalo All-Americans were robbed of the 1921 American Professional Football Association Championship. This was the last year before that organization rebranded as the National Football League. At the time the league had no “playoffs” or “schedules.” The championship was simply awarded to the team with the best record. In 1921 that was the Buffalo All-Americans until Chicago Staleys’ owner/player/coach George S. Halas took advantage of the unfixed schedule to win a couple extra games, tie Buffalo’s record, and successfully convince the league they’d earned the title.

THE ROCKPILE

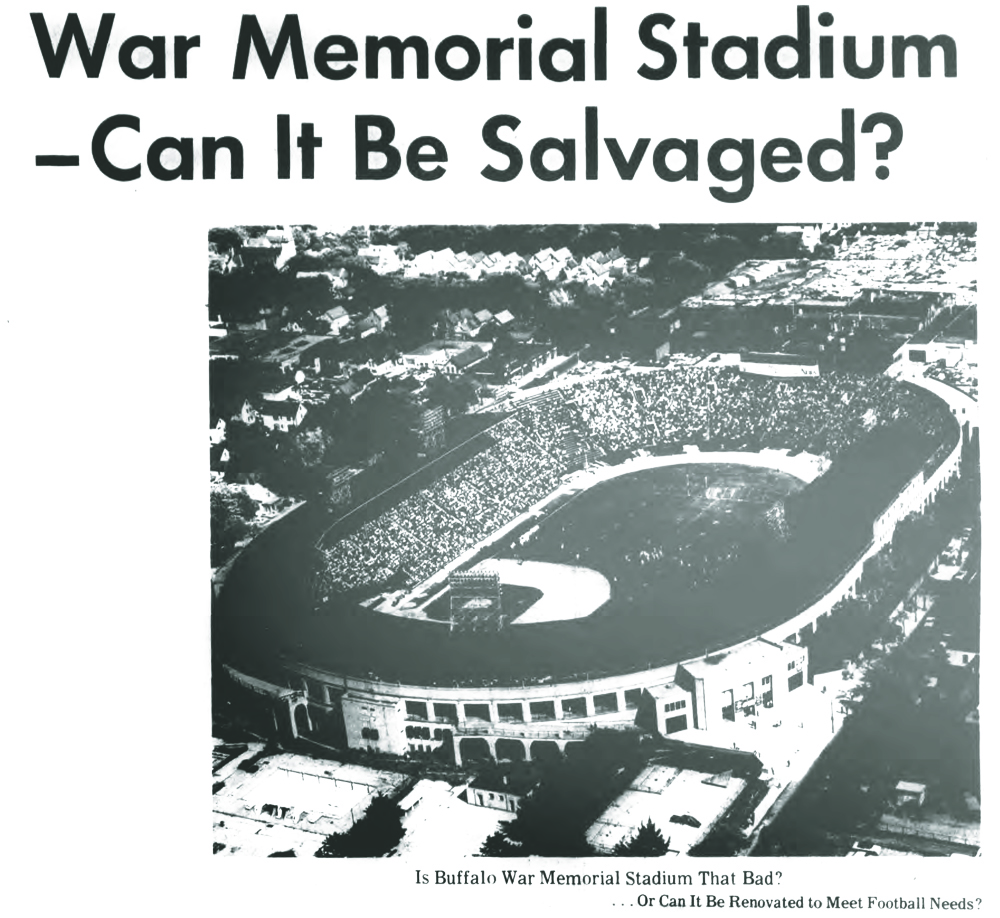

It is here, at War Memorial Stadium, that the Buffalo Bills lost their first home game against the Denver Broncos on September 18, 1960. War Memorial, under 30 years old, was already criticized as outdated and in disrepair while shortages on bathrooms and parking created further problems. In 1969 Lockport sportswriter Brock Yates wrote for Sports Illustrated that it “looked as if whatever war it was a memorial to had been fought in its confines.”

“Some owners probably would demand a new stadium–-or else. I think I’m practical and recognize the problem. That’s why I think the stadium remodeling is our best solution at this time and under these circumstances.” —Buffalo Bills Owner Ralph C. Wilson Jr.

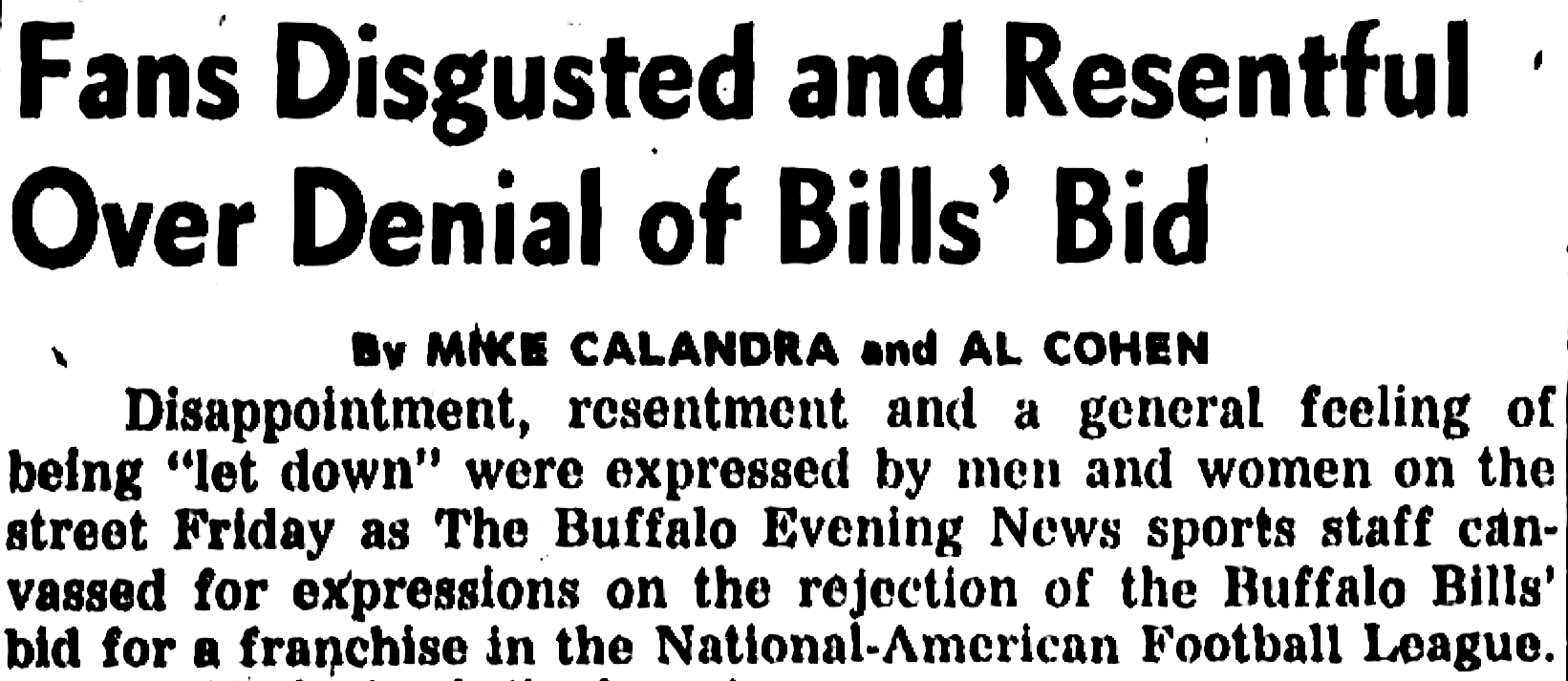

THE MERGER

In 1966 the NFL announced a merger with the AFL which would be complete by 1970. One condition of the merger was that all stadiums required a capacity no less than 50,000 seats. Coming off back to back AFL Championships the public and the government were ready to invest in the Bills and talks of a new stadium began in earnest.

Brock Yates wrote “It is situated in the heart of Buffalo’s substantial ghetto, an area that was racked by riots [sic] in 1967” adding to a long local tradition of criticizing the problems of Buffalo’s East Side without taking any time to mention the systemic socioeconomic architecture that created those problems. As with so many other projects over the past 60 years the region turned its back on the East Side.

THE PLANNING

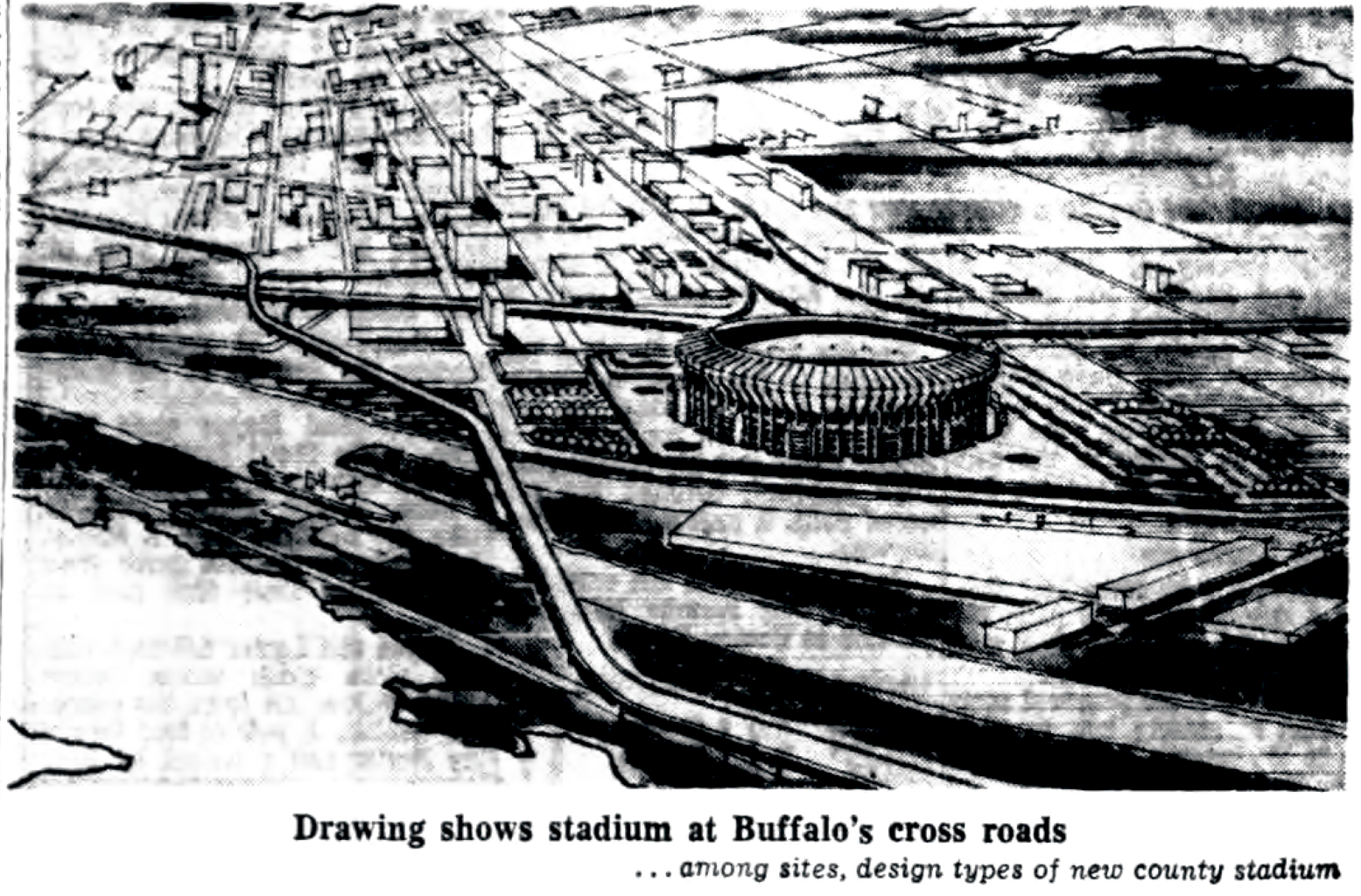

A joint committee was formed between the Buffalo Chamber of Commerce and the newly formed Erie County Legislature to oversee the stadium. They were tasked with answering three main questions: What to build, where to build it, and how much to spend? A 1967 study proposed three sites and four types of structures from a $21 million open collegiate stadium to an $84.6 million dollar dome. The 3 locations were McKinley-Milestrip in Hamburg, Amherst near the new UB North Campus, and downtown at the foot of Main Street.

“Out here in the suburbs we also talk about the stadium,” an anonymous Tonawandan wrote to the Courier Express in 1969, “I have yet to talk to a single person who is remotely interested in a structure at the Crossroads. It is generally regarded as a rat-infested, traffic jammed area, subjected to car vandalism and mugging.”

THE LANCASTER DOME

While half the debate hinged on location and the matter of accessibility to public transit against space for parking the other half addressed the choice between an open stadium and a dome. Although Ralph Wilson vocally opposed indoor football a domed stadium came with the promise of Major League Baseball. The National League was expanding and gave Buffalo the impression that a domed stadium would grant them access to big league baseball, which is a story all its own.

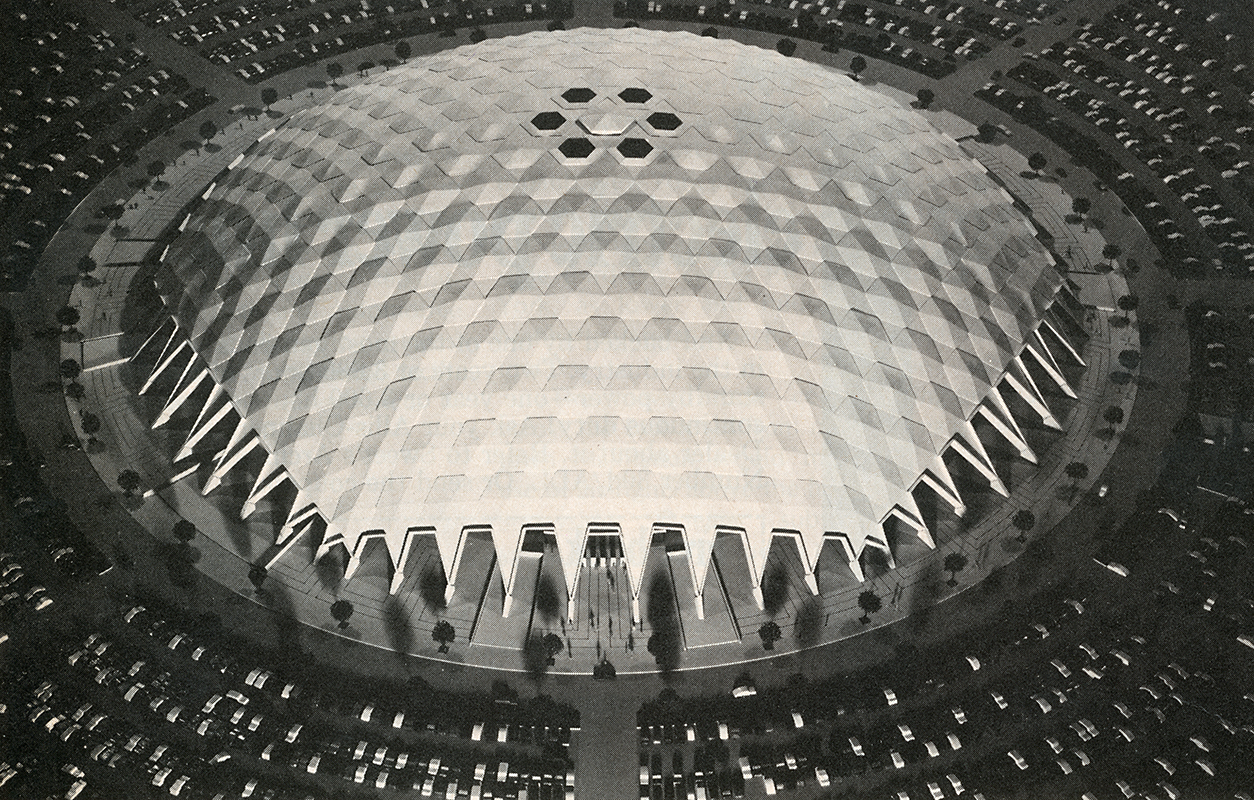

In 1968 local activist architect Robert T. Coles proposed a geodesic dome to be designed in collaboration with renowned architect Buckminster Fuller. Coles told County Officials the dome “could be a symbol for the Buffalo area similar to the gateway arch in St. Louis, and world focus on the exciting development emerging around us.” A presentation given by Fuller for county legislators was arranged which Coles recalled stating “Bucky droned on for almost three hours, lost most of the legislators, and perhaps the project.”

Another Geodesic dome was proposed by the firm of Turley, Stievater, Walker and Mauri. Their dome got attached to a Lancaster site which gained popularity quickly. West Seneca Car Dealer Edward H. Cottrell’s Kenford Co. had purchased a sizable amount of land in Lancaster and proposed to donate 178 acres for Erie County to build a domed stadium on. Kenford’s end of the bargain would be a 20 year contract to manage the site and the development of Cottrell owned land would increase in value due to the adjacent stadium.

After agreeing to terms with Cottrell the County committed $50 million to the project. When the lowest bid came in at $72 million the County balked. Cottrell sued the County for breach of contract seeking $495 million in damages. The County argued that the contract was nullified when the cost exceeded the initial estimates. The whole debacle would play out in many courts. Ludera and Pordum were sentenced to three years in prison on bribery (They served less than 1) and It took 20 years and 10.2 million dollars for the County to settle Cottrell’s suit (not to mention legal fees). Erie County’s credit rating was damaged for years to come, and the Bills were getting closer to finding a new home even further from Buffalo.

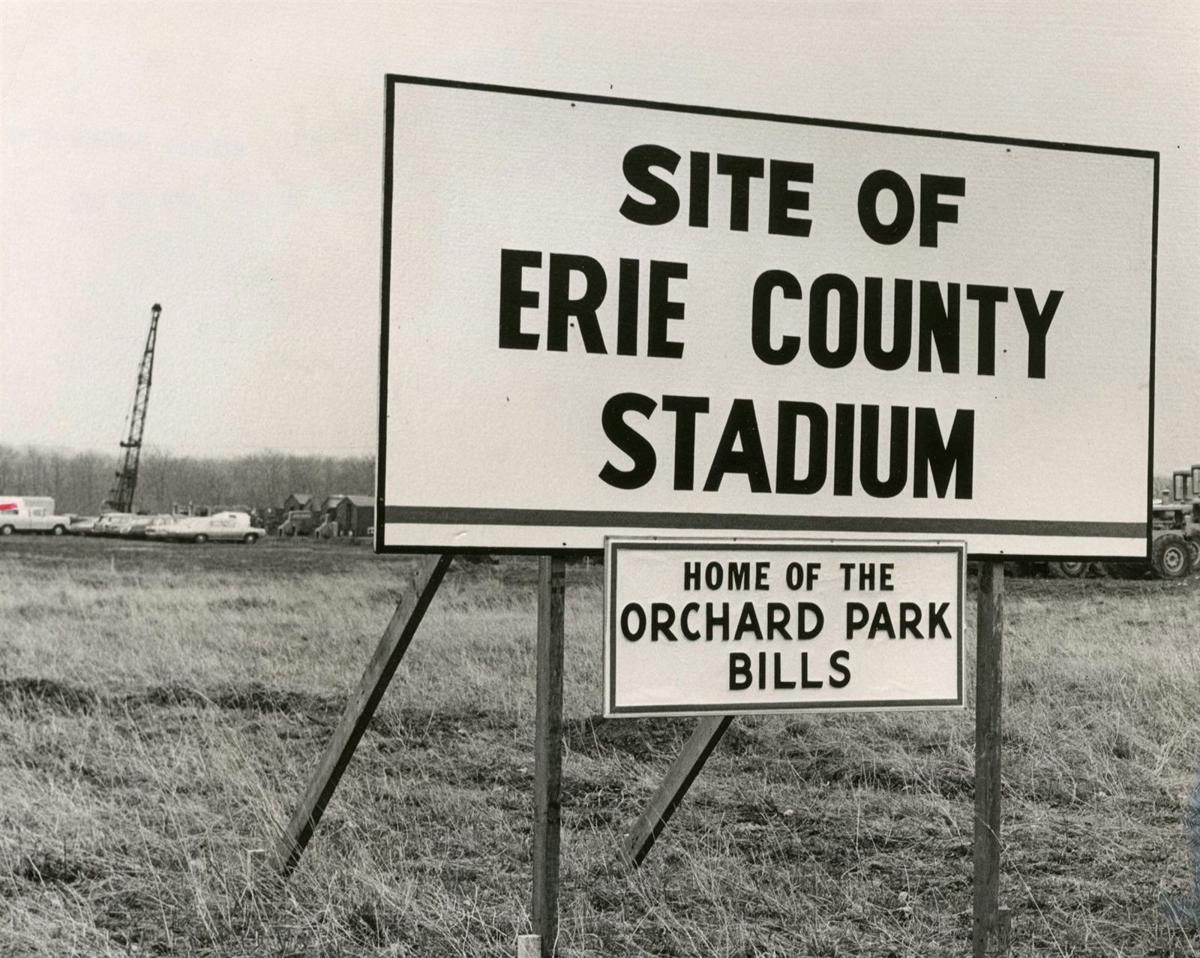

THE ORCHARD PARK BILLS

By January 1971 Ralph Wilson had issued a statement asserting “The climate for a suitable new stadium in the immediate future does not exist in Buffalo. This leaves the Bills no alternative but to move.” Having already met with civic leaders in Seattle Wilson turned his attention westward and Erie County scrambled.

In April 1971 a proposal was made for the stadium to be built on land in Orchard Park the County had allocated for a community college. By September the Erie County Legislature approved 23.5 million dollars for the Orchard Park Stadium. On April 4, 1972 dynamite sounded the ground breaking on what would become Rich Stadium.